There came a time in the 1990s when my dad told me that the movie Network (1976) used to be an outrageous satire, but now it was just prophetic. Once an absurdist comedy, it had transformed into stark realism as the world went wrong and met its strangeness.

I eventually made my way to the local family-owned video store (yes, that long ago) and checked it out. I remember watching it for the first time and simultaneously trying to imagine what it would be like for my dad watching it in the 70s: in that film, it’s supposed to be outrageous that the executives of broadcast television networks would be a-moral gods, or that terrorist groups would have media strategies, but by the 1990s these ideas were no longer “funny because they’re absurd,” and they had even become “no longer funny” because they’re absurd but true — emotionally bitter, like annoyance.

I was thinking about this as I sat down with my kids to watch The Truman Show (1998). Our family has been playing this little “family movie night” game where we each put the name of a film in a bag and then have a drawing — every movie gets drawn eventually — and no matter what you feel about the movie, you have to sit and watch it, them’s the rules. It’s been really good for giving the whole family more of a shared cultural context (ie: we’ve watched the same things so we get each other’s references), but I’ve also used it to expose my kids to movies they might otherwise not see, but which I think have cultural resonance. That’s why I picked Ferris Bueller’s Day Off and that’s why I picked Beetlejuice. And that’s why I picked The Truman Show, which I hadn’t seen since I watched it in the theaters the year it came out, three decades ago.

Like Network did in the 70s, The Truman Show takes the 90s media environment and exaggerates its worst excesses into absurd comedy. But also like Network, there are aspects of the storytelling that take on new meaning a quarter of the way into the 21st Century. Just as the idea that terrorists work the media seemed over-the-top in the 1970s but a miserable banality of modern life in the 1990s; the idea that people’s “real lives” and “fictional roles” no longer have distinction seemed over-the-top in the 1990s, but now it’s a sad fact of life. Today, people perform their whole lives online for money, and while you can still claim that’s “absurd,” it is also, now, all-too-real.

In the film, Truman’s birth is basically a reality show competition — he “won” because he was the baby who “arrived on cue” to start the show. This infant’s “prize” was being legally adopted by a corporation and having every moment of his existence broadcast worldwide. Actors are cast to be Truman’s parents, and they really have to raise him, always on camera, even as they take direction and have their lines fed to them via an unseen speaker in their ears.

A child actor is cast to be Truman’s best friend, and they really do grow up together, but always with the friend, “Marlon” (not the actor’s real name) aware of reality, taking direction, reciting lines, while Truman is not. It is an enduring deception that comes from everyone Truman knows. Even strangers passing on the street are agents of this false reality. But the actor playing Marlon “grows up” with Truman, lying to him all the way.

Another actor is cast to be Truman’s “love interest” and she has to marry him, and have sex with him, in hopes of the first “on-air conception” in television history. (The camera always pans to the window where the drapes dance in the breeze — the classic cinematic cypher encoding unseen sex.) She also has to occasionally position products towards the hidden cameras and recite ad copy. It’s clear (to us and to Truman) that she doesn’t particularly care for him — she’s just doing her job — yet the meet-cute is written and the circumstances are manipulated to assure their marriage. Truman’s “choices” are the choices of a pigeon in a Skinner box.

Everyone involved is degraded as they are elevated to fame, even Truman, who is an innocent. And so the film shows how elevation to fame IS degradation. It is also deception, lying not just to others but to yourself. Because while Truman doesn’t know the true nature of his world, he does seem to know that everyone’s fake. He doesn’t at first realize that it’s all for him — he seems to think that fakeness is just how people are, and so he follows suit. He has to discover what it means to be real like an explorer entering a vast, dangerous, uncharted canyon.

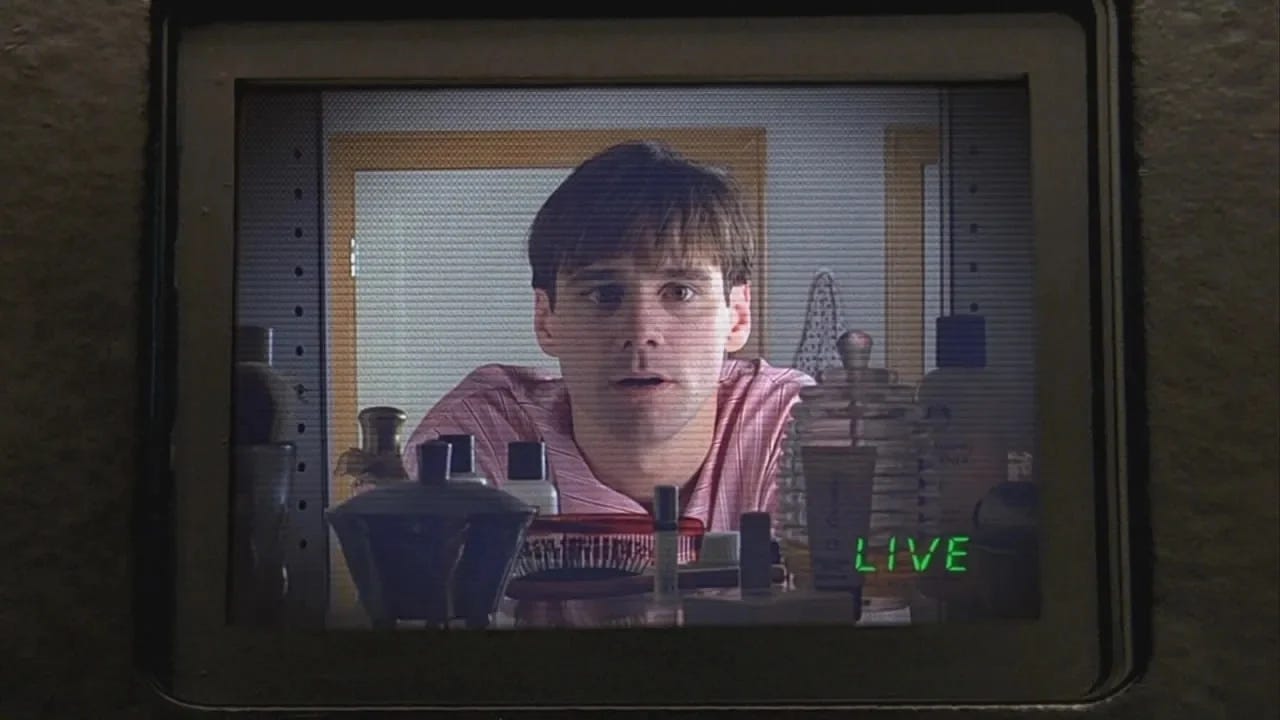

The film is filled with cuts to fans: an older couple adoring Truman from their couch, a middle-aged man watching Truman from his bath tub, two security guards watching Truman on the job, and a whole bar/restaurant of Truman fans, in the model of a sports bar, where the televisions are always tuned to the Truman Show and occasionally bets are taken on Truman’s next actions.

What’s remarkable (spoiler) is that, at the end, when Truman escapes from his pretty prison, all the fans CHEER for him — they are not sad or upset to see him escape the confines of his “show” despite this meaning the end of their entertainment — and we realize that — whether they knew it or not — what they’d been watching for, wanting, all along was for Truman to figure out the truth and escape. Perhaps the appeal of “The Truman Show” for them was not voyeurism but identification — they too recognize that they live in a world full of deceptive surfaces, they too desire escape. Truman’s escape is a global catharsis — but not a life-changing one, because it’s just entertainment. The film ends with the two security guards finishing cheering for Truman and then (beat) reaching for the dial and asking “what else is on?” Because even tho everything that happened was Truman’s LIFE, and even tho people were obsessed with watching it, in the end, it was just entertainment, and it was easily dismissed and moved on from.

This is the diminishment: becoming someone else’s entertainment means that the value of your reality is publicly debased, because it’s placed into the palms of innumerable hands who really don’t care. They might watch, but they don’t respect. They might feel, but they feel insomuch as the character represents them.

This dynamic shows us the value of privacy, and there’s an amusing nod to this in the film when Christof, the director who runs “The Truman Show,” allows a rare interview. The interviewer thanks him, and points out that, as everyone knows, he jealously protects his privacy. Ha-ha. But also not ha-ha. Of course the person responsible for exposing another person’s entire life for entertainment would be deeply private — we see this today with the likes of Mark Zuckerberg and the other Silicon Valley privacy pirates: they have built empires on at-scale exploitation, and so are exquisitely sensitive to the tragedy of being exploited. It is absurd but no longer absurdist comedy — it’s an absurd, and sad, feature of our reality.

My kids have grown up post-broadcast-television. Everything they watch is via Netflix and Disney+ and so on. Instead of “seeing what else is on,” they choose from endless menus. Instead of callers dialing a 1-800 number to get screened in hopes of proffering a question to the deeply private auteur, everyone crafts a comment (and then braces with dread-hope for its potential virality). Yet just as the filmmakers intended all those years ago, my kids found the film disturbing — they wondered if they were on a show or if everything were real. Imagine how much more disturbing it would be for them if I were the type of parent who put them online?1 If they knew that sometimes their “ordinary life” was getting “likes” and comments and being shared? Well, then, they would always be sort-of performing, wouldn’t they?

I’m proud of the fact that when I try to take a picture of my kids at vacation spots they stick out their tongues and give each other bunny ears and can’t hold still and just in general act like kids — because I’ve seen the other kids, the ones who are eerily well-trained, who pose so still and perfectly, who check their hair and hold their heads just right, and do as many retakes as mom requires until it’s Insta-worthy. The only complicating factor for my kids’ future sense of reality is that they will be sharing the world with those performers. And so we’ll still have to ask was the marriage real or for clicks? Is that lifelong friendship actually a “collab”? Are your parents really your coworkers, agents, brand-managers?

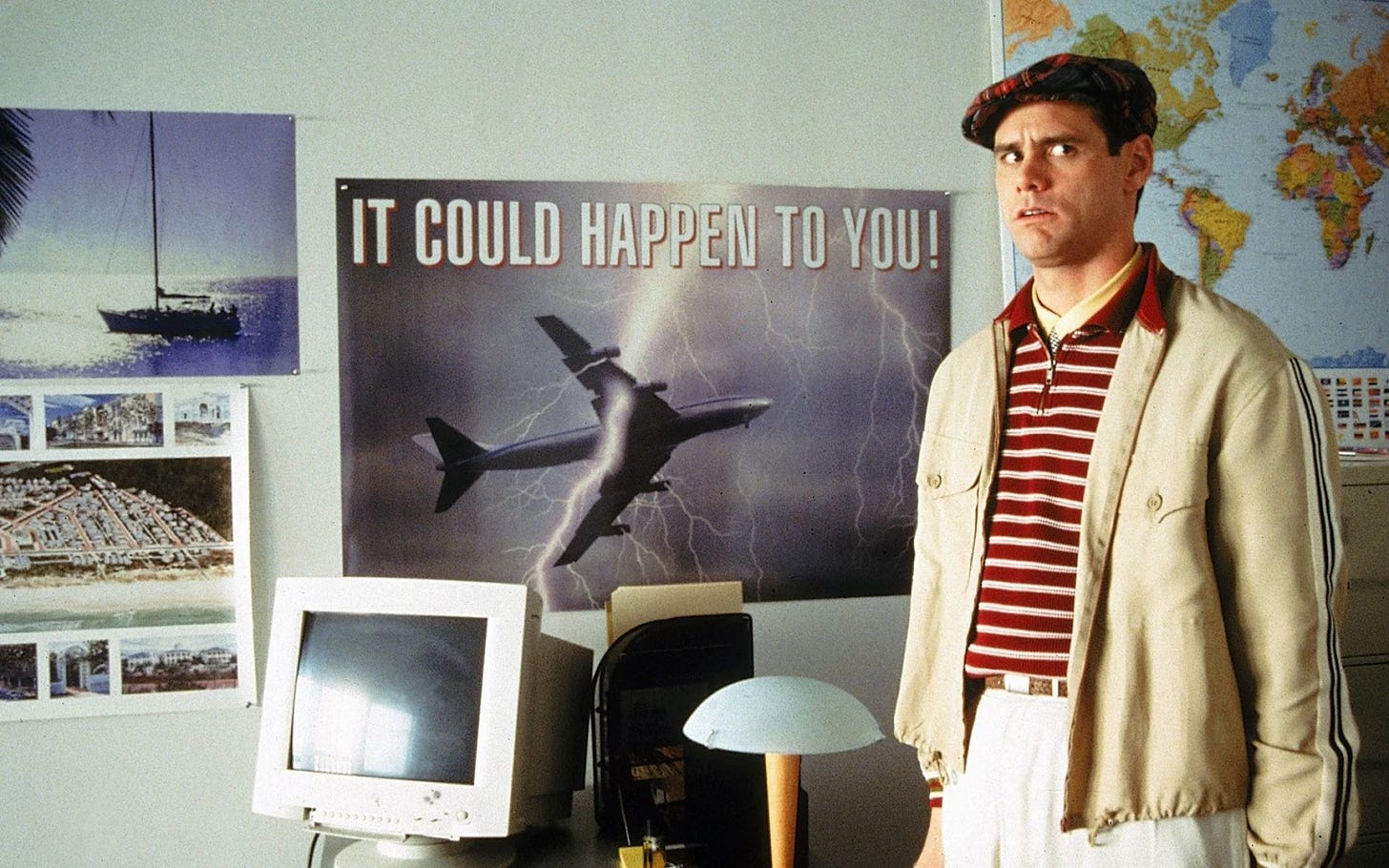

The part of The Truman Show that really struck me on this re-watch, tho, was something else. It’s always the thing you forget that comes back and smacks you in the face. A key part of the story is that Truman must be prevented from getting too curious about the world or wanting to travel. And so from a young age they manipulate his environment so it’s full of terrifying reminders of the dangers of the outside world. When he pushes too hard for adventure as a kid, they kill off his father; when he finally finds a way to escape, they nearly kill him. There’s a “travel agent” in town whose office is comically papered with posters designed to dissuade you from travel, like a plane being struck by lightning alongside the words “IT COULD HAPPEN TO YOU.” Truman has been trained to be fearful — he’s surrounded by safetyism on all sides. It’s in the language the actors around him use — his “father” saying “it’s not safe” and his “wife” saying “we have to think about the future!” It really drives home how our contemporary culture of safetyism can be used as a means of control.

Full disclosure: when they were babies I did have a private Facebook group for their admirers — a “fan club.” I saw the error of my ways in 2018 and deleted everything.

I've never heard of “safetyism" as a concept, but it really hits home as a woman, especially. The constant messaging of "be safe" and "think of the future" is such an insidious way to prevent one from exercising free will or questioning the status quo.

Never seen this one but have intended to watch it for research on a new project.

Every future dystopia comes true. Demolition Man just happens to be the most accurate.