In July ‘25 this Substack publication will reach 5 years old. Yep, it was 2020, in the pits of the pandemic, when I came to this then-new online space and decided to build something for HUMANS living in an ever-more POST-HUMAN world.

Since then, artificial intelligence has become a preoccupying subject for almost everyone in the world. So I just wanted to say: FIRST! Just kidding. I wasn’t first. When I teach my AI in Fiction class each Spring I usually start by taking my students all the way back to 1872, when Samuel Butler published Erewhon, or more specifically I take them thru a sub-section of Erewhon called “The Book of the Machines” in which we hear arguments against allowing machines to evolve — because they will outstrip and enslave humankind. Fun! :)

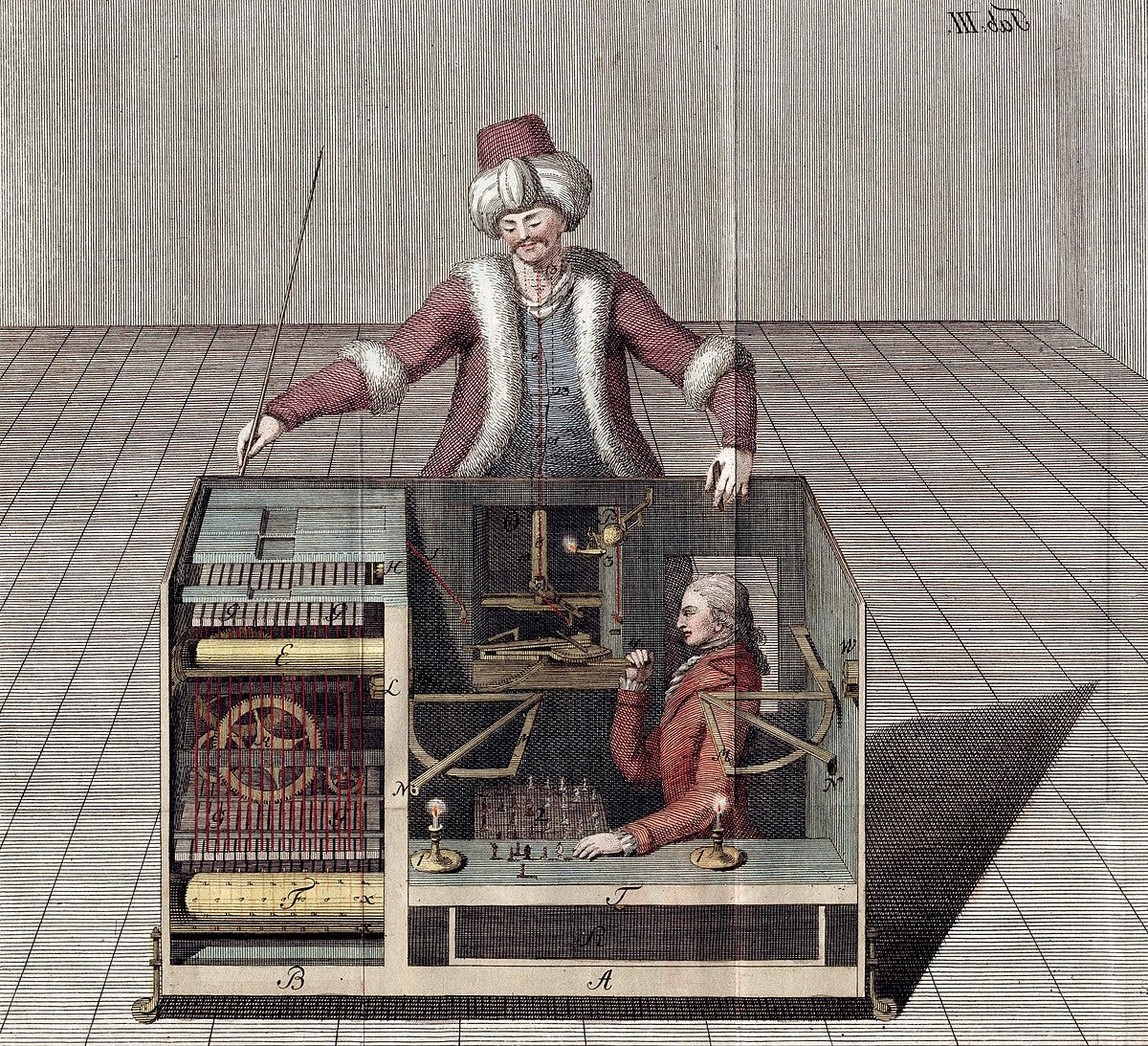

But this Spring, I think I’m going back even further, to 1770, to tell the story of an artificial man, an “auto-man” (in the shape of an Ottoman) who tortured the imaginations of Europeans and Americans for 84 YEARS.

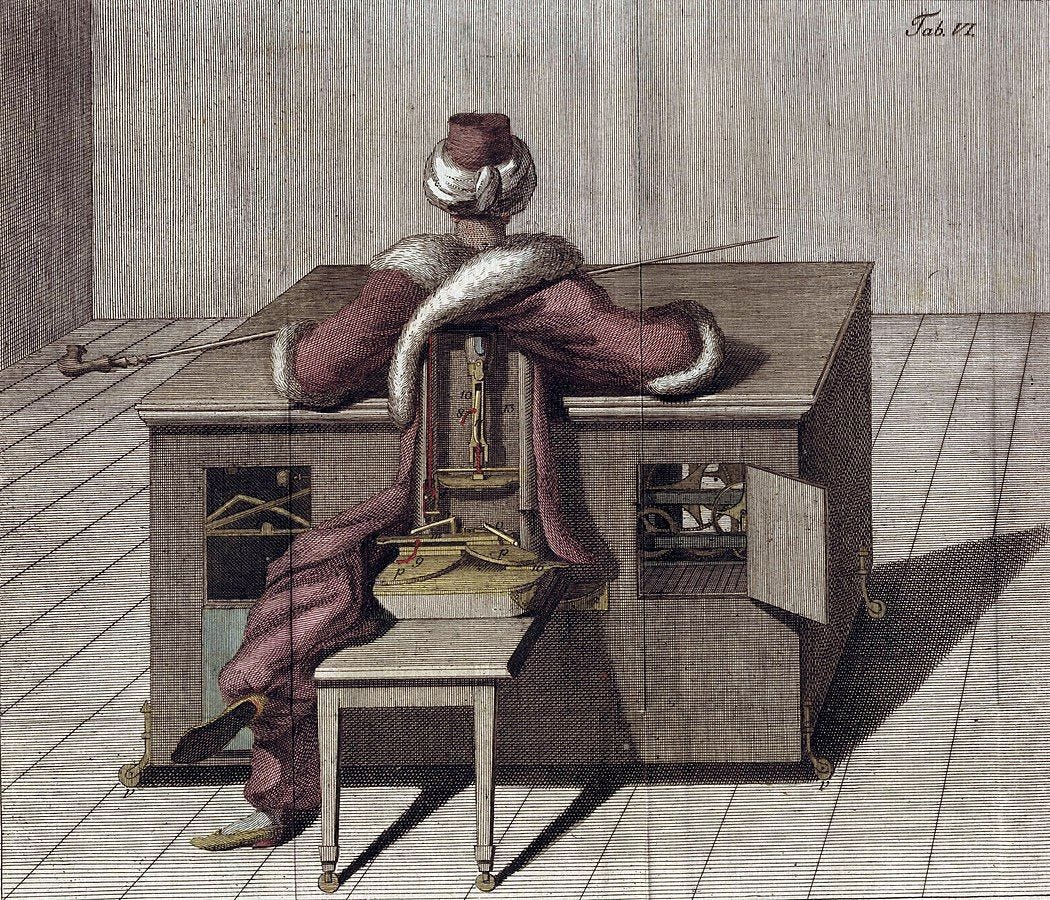

I speak, of course, of “The Mechanical Turk.”

“Mechanical Turk” is the name the machine is best-known by today, but that’s because of Jeff Bezos’s bizarre sense of humor and rock-solid sense of marketing. In 2005, Amazon created a platform where humans could request jobs be done for small amounts of money, and humans could do the jobs for ever smaller amounts of money, and the platform would disembody the entire exchange so that it seemed like “a machine” was doing something sort of “amazing for a machine,” but really a human was behind the machine, doing something “fairly mundane for a human.” They called this “artificial artificial intelligence.”

What better name for their platform than a callback to history’s greatest “artificial artificial man”? The seeming-machine that seemed to play chess? And this was no minor hoax! By the time Edgar Allen Poe published his essay about what was then-called “Maelzel’s Chess-Player,” the hoax had been ongoing for 66 YEARS (and would continue for almost two decades more). As Poe complained in his essay:

Wherever seen [the chess-player] has been an object of intense curiosity, to all persons who think. Yet the question of its modus operandi is still undetermined. Nothing has been written on this topic which can be considered as decisive — and accordingly we find every where men of mechanical genius, of great general acuteness, and discriminative understanding, who make no scruple in pronouncing the Automaton a pure machine, unconnected with human agency in its movements, and consequently, beyond all comparison, the most astonishing of the inventions of mankind. And such it would undoubtedly be, were they right in their supposition.

Poe was skeptical, as were many who encountered the chess-playing “machine,” and Poe was also clearly annoyed that the public was being taken in by this ruse, but he was unable to explain how the damn thing worked, even if he was capable of tracing its history and casting tremendous doubt. He did proffer some good guesses, but those guesses turned out to be as right as they were wrong. Poe acknowledges in the essay that he’s guessing, and he’s more concerned with making the distinction between “mind” and “pure machine”: the moves and other actions of Maelzel’s Chess-Player, he insists, are the result of a human mind, not a mechanical action — on this point, Poe was correct.

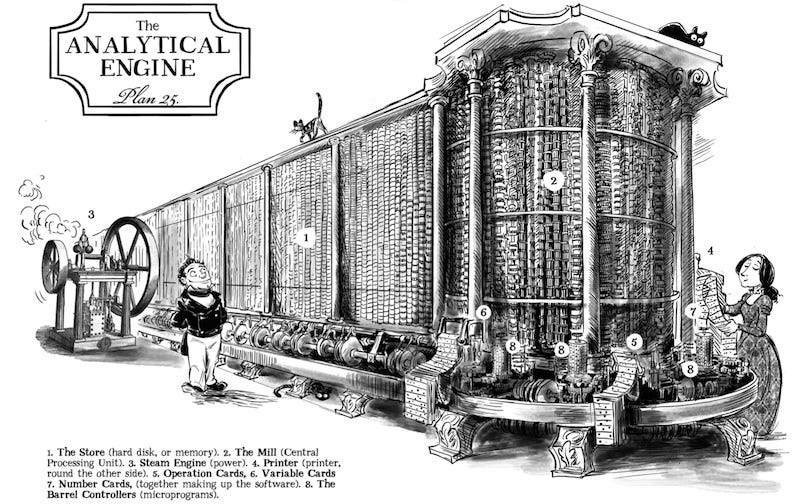

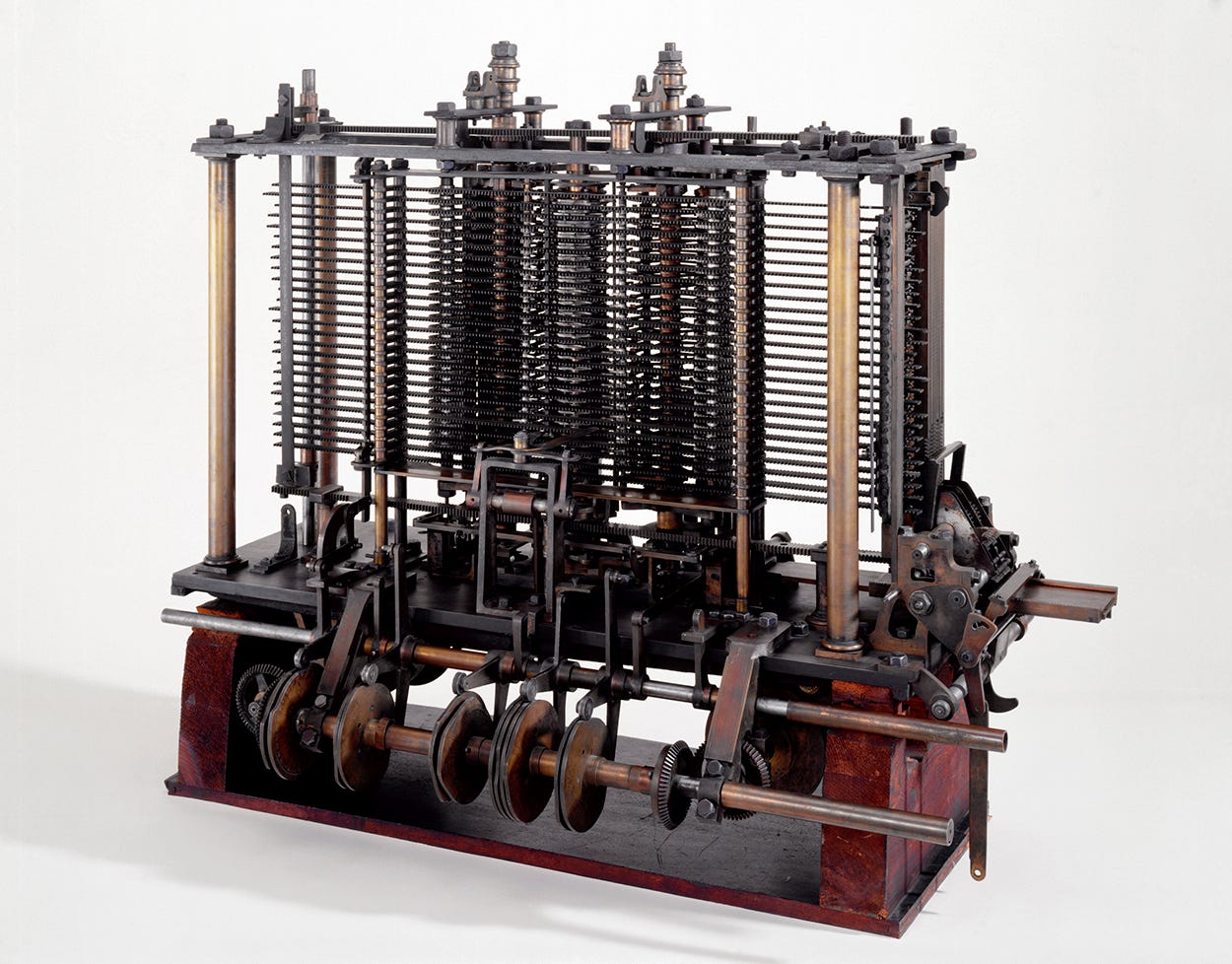

By 1836, when Poe was writing, “Babbage” was a household name: Charles Babbage (1791-1871) was an eccentric mathematical genius who held Newton’s chair at Cambridge, and is still today credited with designing and inventing the first computer, “The Analytical Engine,” even tho he never finished building it. Steampunk fans hold onto your goggles, it was designed to be programmed using the same principles as the Jacquard Loom1, and had it been built, it would have been enormous, like a moderately-sized train, a dazzlingly complex system of gears and pegs and levers designed to compute not just numbers but anything that could be rendered symbolically.

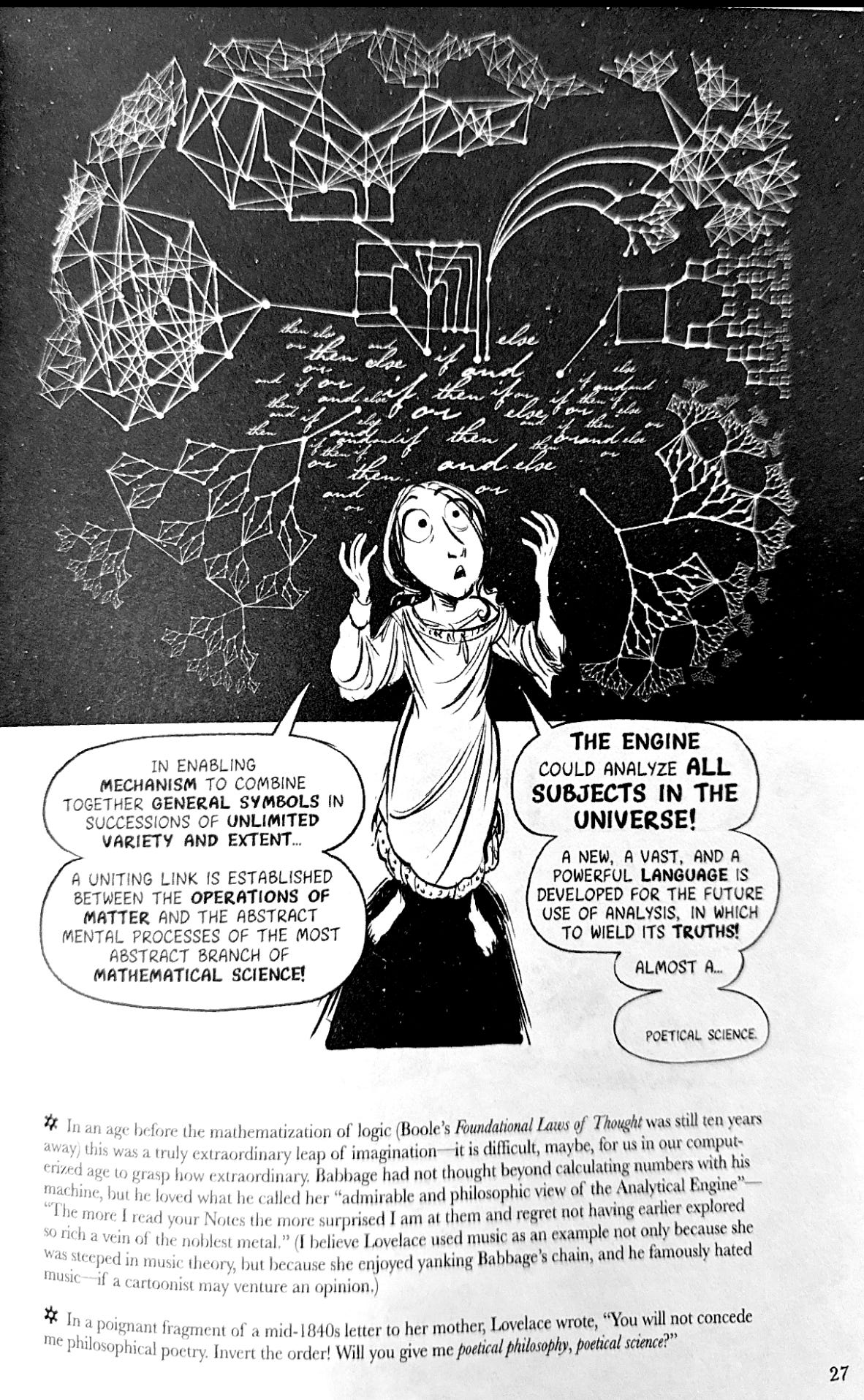

This last innovation was thanks to the genius of Ada Lovelace, today regarded as the first computer programmer, who realized the potential for computing beyond just numerals.

Sadly, Lovelace died of cancer very shortly after publishing her first (therefore, only) paper on the subject, and Babbage’s work languished. Sydney Padua’s graphic novel The Thrilling Adventures of Lovelace and Babbage imagines an alternate universe where she doesn’t fall ill and their machines are built and programmed, and the two go off on thrilling adventures. But that’s another story. :)

Babbage did complete a portion of the smaller, simpler “Difference Engine,” which was capable of performing vast and tedious computations to create tables that were useful to navigators and such. This was the bleeding edge, in 1836. This was the state of the art.

When Poe was casting his skeptical eye on Maelzel’s chess player in 1836, Lovelace was still alive, and she and Babbage were close friends conspiring to build the world’s first computer. While Lovelace was relatively unknown outside of Babbage’s impressive social circles (which included Charles Dickens, Florence Nightingale, Alfred Lord Tennyson, and Charles Darwin), Babbage was world famous as the man destined to build the world’s first computing machine.

So when Poe compares the spectacle of “The Mechanical Turk” to “the calculating machine of Mr. Babbage,” he’s referring to the highest high-water mark for technology in that age — so high, in fact, that (even tho no one knows this yet), Babbage himself will not be able to achieve it!

There is then no analogy whatever between the operations of the Chess-Player, and those of the calculating machine of Mr. Babbage, and if we choose to call the former a pure machine we must be prepared to admit that it is, beyond all comparison, the most wonderful of the inventions of mankind. Its original projector, however, Baron Kempelen, had no scruple in declaring it to be a “very ordinary piece of mechanism — a bagatelle whose effects appeared so marvellous only from the boldness of the conception, and the fortunate choice of the methods adopted for promoting the illusion.”

So, Poe asks, should we believe that an accomplishment far outstripping the most ambitious computing project of the 1830’s is being carted from town to town and demonstrated in a side-show atmosphere for a nickel a head? Especially given that the man who actually BUILT the damn thing referred to it as a “bagatelle” — a trifle?

So we travel back further, 20 years before Charles Babbage was born, 40 years before Poe was born, 45 years before Ada Lovelace was born, to the time of Wolfgang von Kempelen (who was not a baron as Poe says, but that was widely believed misinformation at the time). Kempelen was a Habsberg courtier, a civil servant of the Austrian Empire who was also a bit of an adventurer and a tinkerer. In 1769 he observed the Bohemian Queen2 Maria Theresa be impressed by a magic trick, and rather competitively promised on the spot to bring her a magical performance that would impress her even more! Six months later he arrived with “The Turk.”

Needless to say, the Queen loved it.

But Kempelen wasn’t prepared for just how big a smash his “Turk” turned out to be: suddenly he was being summoned by other royals, or, rather, the “Turk” was. Kempelen’s calendar was bursting for years as he escorted the “Turk” to meet Napoleon Bonaparte, Benjamin Franklin, and yes, Charles Babbage, all of whom played against the machine.

The most amusing of these stories is definitely Napoleon’s: in his first game with the “Turk” Napoleon tried to cheat. The machine first gently corrected him, and took away his turn. When Napoleon attempted the illegal move again, it removed the piece from the game. And when Napoleon attempted a third illegal move, the “Turk” brushed his arm sideways and wiped the pieces from the board. Napoleon was amused and asked for another game — which he lost.

All who encountered the “Turk” tried to figure out how it worked. It’s builder, Kempelen, tired of the ruse quickly. He didn’t want to go into the entertainment business, he’d only wanted to impress his queen. Kempelen is said to have revealed the secrets to the trick only to the King of Prussia, who expressed disappointment upon learning the truth, but nonetheless kept the secret. Maybe tricking the world’s most powerful people OR making them sad should you tell them the truth didn’t feel all that great to a dyed-in-the-wool courtier?

In his final years Kempelen retired the “Turk” and refused all offers to buy him. After he died, his son sold the machine to Johann Maelzel, who was also a maker of machines and automatons, but who had more of a taste for the showmanship side of things. Maelzel took Kempelen’s Chess-Playing machine on tour throughout Europe, England, and the USA, and had quite a good run of things.

The fun lasted two years past Poe’s literary take-down — Maelzel took the “Turk” on tour to Havana, where his very close friend, the chess-master and, yes, let’s cut to the chase, “Turk”-operator, William Schlumberger, died of yellow fever. A despondent Maelzel drank himself to death3 on the boat and never made it home. The “Turk” then became the property of the ship’s captain, who sold it to a friend of Maelzel, who then sold it to Edgar Allen Poe’s personal physician, John Kearsy Mitchell, who then created a club for enthusiasts who financed its restoration so it could be exhibited once more. In 1840 the “Turk” was again in public. Thirteen years later, the group donated Kempelen’s now-83-year-old machine to a museum, where it sat in a corner, unmoving. The museum caught fire the next year, reducing the “Turk” to mere memory.

With the “Turk” gone, Poe’s former physician’s son, a man named Silas Mitchell4, published an article revealing the secrets of “The Turk” (or “Maelzel’s Chess-Player,” or “The Mechanical Turk,” — or Kempelen’s magic trick, as you prefer). Poe didn’t live to read it, but he was not too far off the mark. He’d certainly pinpointed who was in the box: he names Schlumberger in his essay as the prime suspect, based on his observation that while this strange little fellow named Schlumberger always travels with the Maelzel and the machine, during exhibitions he is never to be found — the whole Superman-Clark Kent thing, never in the same place at the same time! But as for how the player in the box moves around to avoid detection during the opening display, and how the player manages to “see” and understand the opponent’s moves, and how the player responds to them, Poe had underestimated the complexity of the mechanism.

It often seems this way to me, with magic tricks: it’s not that what the magician is doing is inconceivable, it’s just hard to believe that someone would go to so much trouble for such an unimportant-seeming result. In this case, the most astonishing details are probably that the chess-playing human occupant of the box could not “see” the board from above but instead was clued into the movements because the underside of the board had magnets attached to strings dangling from each square — so each piece’s movement would attract or slacken a magnet. The occupant had a second, tiny, board built into the cabinet that worked as a “peg board” to hold each piece in place, so the player could translate the movements of the magnets into something more fully comprehensible. This same peg board controlled the movements of the arm by means of a pantograph, making sure that the arm approached the right square, picked up the right piece, and moved it to its correct new position. Oh, and, because the occupant required light, the inside had to be fitted with a candle and an exhaust system to emit the smoke through the top of the head of the supposed-automaton Ottoman. Here’s a video that shows pretty nicely how it was done.

But the “Turk” wasn’t done yet: in the 1980s an American manufacturer of “equipment for magicians” named John Gaughan (pronounced “John Gone”) decided to rebuild the “Turk” based on the hundreds of books and essays published on it. He worked on it for decades, adding features as he read more accounts of the historical creation. In 1989, an early version of his reproduction played against a computer chess program at the first Los Angeles Conference on Magic History, one of whose themes was “automata.” That is, a human chess-player pretending to be a person-shaped machine that can play chess played against… an actual chess-playing machine.

So is the “Turk” the oldest “fictional AI”? Maybe! And as with all fictional AIs, the important questions have little to do with the technology and much more to do with human nature and our responses to seeming-beings that seemingly-intrude on behaviors we believe are exclusive to humanity.

Can a machine play a game? Can a machine affect my social standing? (Napoleon seemed to think so!)

Can a machine have social standing? (There was a competing “chess-playing automaton” in the US — “the Walker Chess-player” — that didn’t do nearly as well — perhaps because it could not claim to have played the likes of Benjamin Franklin or the King of Prussia?)

Can a machine outsmart me? Can a machine trick me? Can a machine change me?

These are questions we typically ask about other humans — and perhaps forces of nature so great that we might personify them as gods (or monsters). These are the questions the “social animal” must ask about its connections to the network without which we cannot live a human life. It’s a bit strange for us when our tools assume the role of actors in that social fabric.

The “Turk” provoked that uncanny feeling long before machines were capable of playing chess — because the “Turk” was capable of imposing itself within our society and affecting our social fortunes, or feelings.

And when we find ourselves afraid of what horrors and indignities might come with the next technological evolution, all too often it seems that what we’re really afraid of is ourselves… maybe ourselves disguised or mediated thru a platform or placed in a position of superior knowledge, but, still, ourselves.

It’s just like that bit from Futurama’s “The Scary Door”: you take all the technologies and all the trickery and you combine them to make the worst thing you can imagine…

“Turns out it’s Man.”

The Jacquard Loom’s innovation was to automate and regularlize the patterns in woven fabrics using “punch cards.” This innovation put a lot of skilled weavers out of work. In England, the Luddites (followers of Ned Ludd) smashed these machines in protest, and so the government responded with lethal force, and capital punishment, and “transportation”: the punishment of being shipped off to Australia. It’s odd that instead of the word “Luddite” coming to mean “labor activist,” it has come to mean “anti-tech dullard.” But just as the Jacquard Loom was the predecessor of the machine processor, the Luddites were the predecessors of labor activists demanding dignity for working human beings.

Fun fact about Maria Theresa: before “Queen of Bohemia” she was actually the Empress of the whole dang Habsberg empire. I don’t pretend to understand college basketball brackets let alone the historical rules of succession for European royals, but I can only imagine that she was a particularly well-connected “Queen of Bohemia” given her former status of “Holy Roman Empress.”

In most tellings of this story Maelzel comes off badly — a liar, an opportunist, and so on. When some boys snuck backstage and saw Schlumberger climbing out of the box, they got the story to a Baltimore newspaper, and Maelzel threatened to sue, forcing the paper to retract a story that was almost certainly true. He also went thru a litany of other chess-players before finally convincing Schlumberger, who was always his desired confederate, to join him in the US to play chess from within the box. (Schlumberger was, at the time, playing chess for cash, in competition and by teaching paying pupils, at a cafe in Paris known for its “chess scene.”) The complete picture, punctuated by Maelzel’s death by alcohol poisoning in the throes of grief at Schlumberger’s death, suggests a more sympathetic man, someone whose love for Schlumberger (we can never know if it was romantic or of another flavor) was extremely sincere.

Deep-dive moment for lit nerds: Silas Mitchell was Charlotte Perkins Gilman’s doctor — him prescribing her the “rest cure” was the inspiration for her famous short story “The Yellow Wallpaper” in which a woman prescribed the “rest cure” goes absolutely batshit crazy :)

Great piece, Amy! I especially loved this line: "And as with all fictional AIs, the important questions have little to do with the technology and much more to do with human nature and our responses to seeming-beings that seemingly-intrude on behaviors we believe are exclusive to humanity." Always adjusting to what it means to be human!

Oh my, as usual, I learned much from your writing. Now I can go crawl back under my rock.