The Lighted Globes

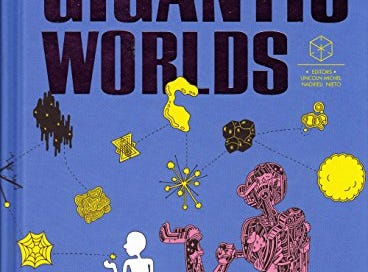

Originally published in the Gigantic Worlds Flash Science Fiction Anthology in 2015

I fashioned the globe panel by panel. Each panel I crafted by hand from what remained of my mother’s house after the fire. A fragment of photograph. A black bubble-charred patch of fabric that was once a doll. Heat-cracked pieces of chandelier. A triangle of bathroom counter that held my mother’s fingernail, its node of flesh, its spot of blood.

I used surgical tools and a laser rule, a dremel with a microdrill and diamond cutter. I arranged worklamps around my desk, and examined each cut through a magnifying glass on extender arm, the kind used by model-makers, but I was not painting toy soldiers, I was putting perfect edges on the irreplaceable refuse that proved I lived, I was born.

When each panel was perfect, I connected it to the last, attaching circuits of gold wire, every panel leading to every other, until the inside of the forming sphere was a network of threads interwoven like the dream of a future city. There was only one panel left to place. Carefully, watching through the glass, I spun the diamond cutter on 10 and dipped it into my wrist. I wiped the blood from the glass, from the skin, tightened the tourniquet, did it again. Soon I had to wipe away bone. Marrow. Screams. I zipped the spinning wheel through the last fleshy connection and the hand was free. I put it inside the nearly-finished globe. It waited: ready. The final panel in place, my hand busied itself inside, attaching the wires. The globe hummed, vibrated. I turned off the worklamps. Yes. As my eyes adjusted I saw it gave off a soft, warm light. Inside, my hand died. But this light, this fragile globe, danced with life: seashell and silk, yarn and balm, buttons and book covers, a mute curl of cello.

When the night grew quiet, I carried the globe down the stairs and out into the city where I live now. Other globes lined the streets, at least a dozen on my block, a hundred more visible farther down the road. Some glowed and hummed as mine did. Some were nearly perfect spheres, like mine. I placed it in good company: two precisely crafted specimens resting beside a crumpled fast food bag, wobbling against the wind. With my one hand I nudged the others away and patted down the bag to form a soft pedestal for my creation.

I looked back a few times as I walked away. How can I say what was in my heart? A woman walked by me, who also had one hand, she seemed to know. But she said nothing because there are no words. That night in bed, not sleeping, I imagined how it could happen: kicked by accident, stomped on purpose, blown into traffic, rolled down a hill into a wall. I imagined a drunk sitting down without looking, hard. Each new terror lifted me from my mattress to the window to look, but I couldn’t see it, it was too far. Still I kept looking, putting my face into the cold night air, the odor of rot rising from the dumpster two floors below. Once, I heard something breaking — the sound was high and crystalline, a shattering that contains a thousand other shatterings. But I don’t think it was mine. In the morning I went down to see, stepping to the cadence of my throbbing stump. I knew before I knew. It was gone, my globe was gone, along with many others who did not survive the night. Their odds aren’t good, out on the streets. Kept at home they die. But mine didn’t survive even one night: it lay crushed, a pile of wire, flesh and trash.

An old man lives in a heap of boxes beside my building. He has no hands, no feet, no teeth, and always in his lap he cradles a dead ball of concrete from which protrudes the half-scrutable edges of things: bits of brightly colored plastic, the corner of a portrait frame, a tangled lock of yellow hair. I walk past him carrying in my arms the shattered mess that was once my globe, and he points one of his stumps at me and laughs. His laughter is hoarse and wet, and blood oozes from his gums onto his lips.

Back in my apartment, I set the tinkling remains on the shelf above my bed. I use tongs to pry out my dead hand and drop it from the window to the dumpster below. Let it rot among the fruit rinds and chicken bones: it no longer matters. I take a deep breath. I switch on the work lights. I dig deeper into the box of things I salvaged after the fire: the nose and mouth of a ceramic doll; a dolphin-shaped belt buckle; an old glass thermometer, blackened and bent, its mercury intact. My remaining hand throbs in time with my stump, but I ignore it. I piece together the first panel with heat and glass and wire.

I decided not to wait to read it. 💜 Still processing, but I think I see what you're trying to illuminate for me. Thank you for sharing this!