The Ethos of AI is a Void

A New Proof against an Old Lie

Among the most basic principles of classical rhetoric is the idea of “the three appeals” — logos, pathos, and ethos. Ethos is not like the other two.

Logos is the appeal to the audience’s reason, and pathos is the appeal to the audience’s emotions. I might argue for the reasonableness of a set of actions, but I might also describe the pitiful suffering that will strike small children to move your heart, more than your head. That’s logos and pathos. Appeals to the reason and feeling that are in you.

Classical rhetoricians generally acknowledged that pathos is more effective in getting results than logos, even if reason is, our reason tells us, more reliable than emotion. Action is stirred via passions.

The same classical rhetoricians would tell you, though, that neither of these is as powerful as ethos, and ethos is different: instead of an appeal to the head or heart of the audience, it is the appeal of the speaker to the audience. A test of trust, if you will.

Your reasoning and your ability to stir passions are (forgive me) “content,” whereas ethos can be partially established through the content of your speech (although trust is easier broken than built!), but it’s also unavoidably established, or eroded, by the speaker, the source, the “container” — the body. Before hearing the words, the audience asks — is this person on my side? Is this person one of us? Do I admire this person? Do I despise him?

I bring this up because computers are composing essays now.

I’ve been teaching college writing courses for over 20 years. Over the same period of time I’ve been submitting short stories and essays for publication. And there’s a sticky old lie that comes up again and again about “the quality of the writing.”

This is not to say that there are not differences in quality of writing. Writing can has its quality differenting right? But at a certain level, most things are “marked off” because of nitpickery and a certain amount of “I’d have said it differently.” Writing is published because it resonates with the editor. Rubrics are subjectivity masquerading as objectivity.

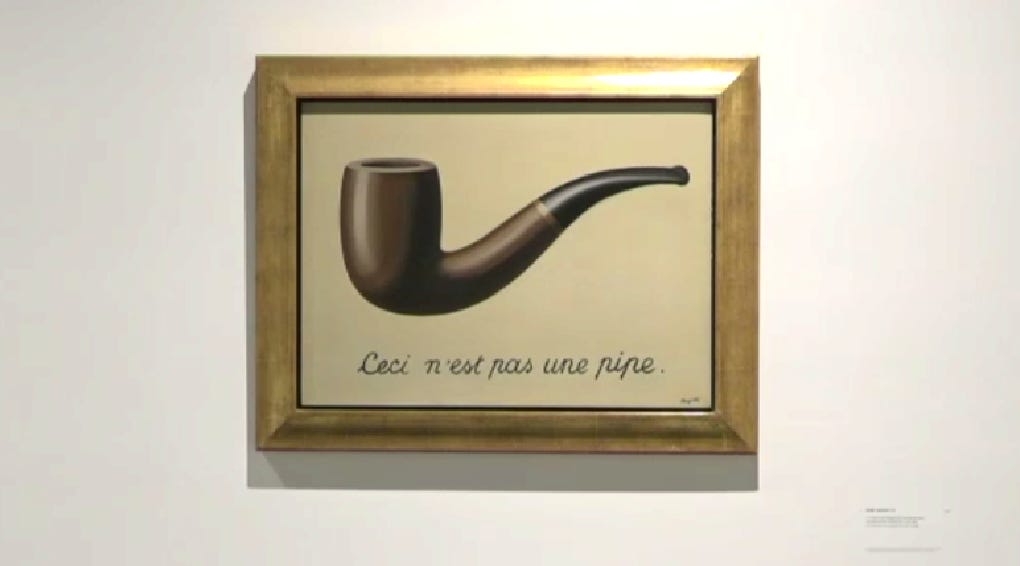

There’s a history of white men succeeding disproportionately in creative writing MFA admissions and literary publication. When institutional gatekeepers have been confronted with this problem, in the past, they’ve often claimed that they don’t look at the identity of the author, but at the “quality of the writing.” In other words, for them, ethos n’existe pas.

Others remain skeptical that you can read a story, poem, or essay and not look at the identity of the author. The submissions are rarely anonymized.

And many of us would argue that you shouldn’t read a story, poem, or essay without looking at the author’s life. Does it matter that Voltaire was rich and Poe was poor? Yes. Does it matter that Willa Cather grew up in Nebraska, and that her family hailed from the pre-Civil War deep south? Hell yes.

Our whole concept of literature and authorship involves understanding the connections between the person and what they wrote: we continue to know and think about the long litany of tragedies that made up Edgar Allen Poe’s life. The fact that Willa Cather lived as a man and went by “Will” for a part of her young life is important to how we read several of her stories. We even imagine an identity for Homer, who might not have really existed, but we need an author, dammit. A story without a known source is like a voice from a void — it leaves us unsettled and wondering.

A story that really has no human source, which has been generated based on patterns in human stories, actually is the voice of the void. To feel or think or know anything in response to its blankness is akin to torment.

There are other interesting cases:

Over a decade ago a college in Texas attempted a first-year writing experiment in which teachers did not grade the essays of their own students. Instead, they coached their students at writing essays, and then graded anonymous essays from other people’s classes on a computer. Each essay would be graded by two instructors whose judgement would be averaged.

This experiment did not last long. It fell apart hard. People quit. Dropped out of the college. It left some participants in tears.

Why? Doesn’t it sound like a good idea? Teachers get to focus on helping their students be better writers, and the writers, presumably, have an “unbiased” audience of readers — and two of them instead of just one! Why did everyone involved in this program hate it?

Well, first, because it reduced the work to “content.”

This experiment created a framework in which the rubric was all the instructors had to go on — they could look at an essay’s reasonableness, they could look at an essay’s charm or wit or vivid description, and to a certain extent they could even look at the essay’s content-based ethos, that portion of ethos that is communicated in the words themselves: appeals to moral high ground and ethical behavior.

They could judge these things. But they couldn’t connect with these things. Because the rest of the ethos was missing. They couldn’t see the essay’s author — even though the author was a living person who might pass them in the hall — while I can see Willa Cather, who died before my parents were born — why?

Consider the point of view of the student: you’ve worked on an essay. You hopefully had something to say. The essay is returned to you with two grades and two sets of rubric notations. Maybe you got an A. Yay. Your words worked out well. But do you feel heard? Who even read this? What are they like? How do they move through life? How might your words have changed them?

Also consider this: how do you judge half of a conversation taken out of context? If a student writes only what their teacher has stated as examples, that is not a great essay, it’s well-organized notes. But only the teacher, the other participant in the conversation, can know that.

That unweildy part of ethos that’s not in the words themselves? That part is also part of the context, and it means a lot. It’s the thing that creates two different meanings when your mother and your boss advise you with the same phrase, or call you “honey.”

Why is a poem meaningful if written by an Asian-American woman but not if it’s written by a white man? Why can John McWhorter write an entire chapter of his book Nine Nasty Words on the n-word, using the word repeatedly throughout?

Even writing it here, I sense myself as pushing the envelope—and feel a need to state that in this chapter I will be writing it freely, rather than “the N-word.” Am I taking advantage of the fact that I am Black, such that etiquette allows me a certain leverage? Yes indeed.

When I read my students’ writing, it’s in a context. I know a facet of who they are, and I know I will see them again. There’s a relationship. That relationship includes obligations, and trust. When I read their writing, I’m far more focused on responding to their ideas — I’m in conversation with them — than I am with judging their adherence to a rubric. This is because I know them as human beings. They are mortal, experiencing minds who move through this world of wonders with hope and apprehension. To regard them otherwise would be monstrous.

What is wrong with chatGPT’s writing? I took the version of the can-you-tell-a-robot-wrote-this challenge in the NYTimes pages and I nailed the difference every time (\brag). The way I could tell was intuitive — it just didn’t sound to me like things people would actually write, and people have already created apps that can identify computer-generated text, which means it’s quantifiable beyond human intuition. But GPT4 is already working at a much more sophisticated level than chatGPT, and it’ll be released soon. Google’s got generative AIs too. There will always be another, and another. Eventually it’ll fool me.

And let me be clear: I object to this. I don’t want to be touched by algorithmically-arranged words.

The problems with computer-generated writing might include it being incorrect or unreasonable. But humans are great at being incorrect and unreasonable.

The bigger problem is that any use of AI-generated text presupposes that the Texas experiment had worked out well and that “the quality of the writing” matters and the person behind it doesn’t, not at all. It presupposes that the goal of writing is to get a score.

This is why some people are worried that chatGPT will “kill” the college essay. To the extent that that “college essay” exists to attain a score, sure, call it dead. (I think it already was dead, but put a few more volts through that corpse, it isn’t any bother.) Writing worth assigning in college is writing worth reading, which is writing that reflects a living and experiencing mind, a unique individual’s journey grappling with ideas.

The primary mode of reading such work is not judgement but critical engagement; “judgement” is the mode of last resort. Critical engagement is what we ask our students to do when we assign a text, and it’s what we do (and model doing) when we read and respond to their writing.

We’re in conversation with them. They write to understand what they’ve learned and what they think of it, and how they respond to it, and what it means in the context of their life. This means that even an analysis must express and communicate feelings as well as ideas — or else why do the ideas matter? Which means their writing is about, in part, that which gives them hope and that which stokes their fears. Our students write to work towards conclusions that will affect the way they live their lives.

Imagine you’re in a conversation. I don’t care if it’s a job interview, a first date, a bedside visit with your grandma, doesn’t matter. You’re in a conversation, talking about something that matters to you, and every time you speak, the interviewer, or date, or grandma, corrects your grammar, or tells you how you might’ve said that better. Too wordy. Punctuation misplaced. Wrong word. Imprecise.

You’d say: I don’t want the job, lose my number, and fuck off grandma.

This isn’t to say editing doesn’t have its place — well-crafted text does use words precisely, tends towards persuasive logical structures, employs effective figures of speech. But if writing has any purpose at all, it is because it is shaped under the personality of the living, breathing human being who wrote it.

And I can’t tell you how many writers I’ve seen blossom only after I promise I will not ding them a point for every punctuation error, after I promise, and they trust, that I’m more interested in what they have to say.

And so in our writing we meaningfully converse. But there are no meaningful conversations with chatGPT. Do I sound biased?

In writing, as in so many things, humanity matters, just as identity does. Humanity, after all, is our ultimate shared identity.

Part of humanity is forming affinity groups, and every time you create an in-group, you’re creating an out-group. Much of AI-related science fiction proposes that AI is another out-group. So when I say chatGPT has no ethos, am I simply being bigoted against chatGPT?

Only if chatGPT experiences a life.

Words mean nothing if they come from an entity that faces neither pain nor death, who can experience neither humility nor pride, and who cannot be moved to tears by a small transcendent moment of beauty, or shattered by the depths of loss.

The ancient rhetoricians had advice for speakers who came to the public with ethos-damaging attributes that might bias their audience against them: a lisp, a foreign accent, a bad reputation, the very young, the very old, and so on. They understood that ethos wasn’t just what you said (or how you said it) but who you were when you said it: what you looked like, how people thought of you.

That advice primarily centered around being unthreateningly humble, and getting the audience to see, if only briefly, the value of your perspective and experience to whatever common ground you share.

A generative AI cannot be humble; so long as we live within capitalism and are expected to work to live, it by its very nature threatens our lives; it has no singular perspective, only a vast bank of data; its experience is its training; what common ground do we share?

It has always been a lie that the written work “stands alone” and our perception of it is unaffected by the identity and biography of its author; text with an AI author is a new way of seeing the problem.

When chatGPT is credited for its writing, it’s in the context of us pointing and marveling, as though watching a donkey thumb-type — but even a live donkey knows pain and pleasure, has eyes and ears and one life to preserve.

Most of what chatGPT produces will not be credited, and even when it’s not gibberish or lies, it will still have emitted from a void impressing patterns of human-ness and taking up a space within our human social system: like a sand-stuffed donkey corpse wrapped in human flesh and a dress, replacing your doctor’s receptionist.

"Words mean nothing if they come from an entity that faces neither pain nor death, who can experience neither humility nor pride, and who cannot be moved to tears by a small transcendent moment of beauty, or shattered by the depths of loss."

*chef's kiss*

Thank you! I'd give this a thousand likes if I could. Just curious if these new technologies will change the way you teach or the conversations you have with students about learning/reading/writing.