Teenage Suicide (don’t do it) - [ Heathers 1989 ]

Understanding teen despair in an 80s teen movie

Warning: references to the 1989 film Heathers, with murder, school shooting, rape, classism, shoulder pads, homophobia, violence, and suicide ahead

I’m not a social scientist, but every death affects me because I am a part of mankind (thanks, Donne!), and so I am keenly interested in the question of why teen suicide rates are going up.

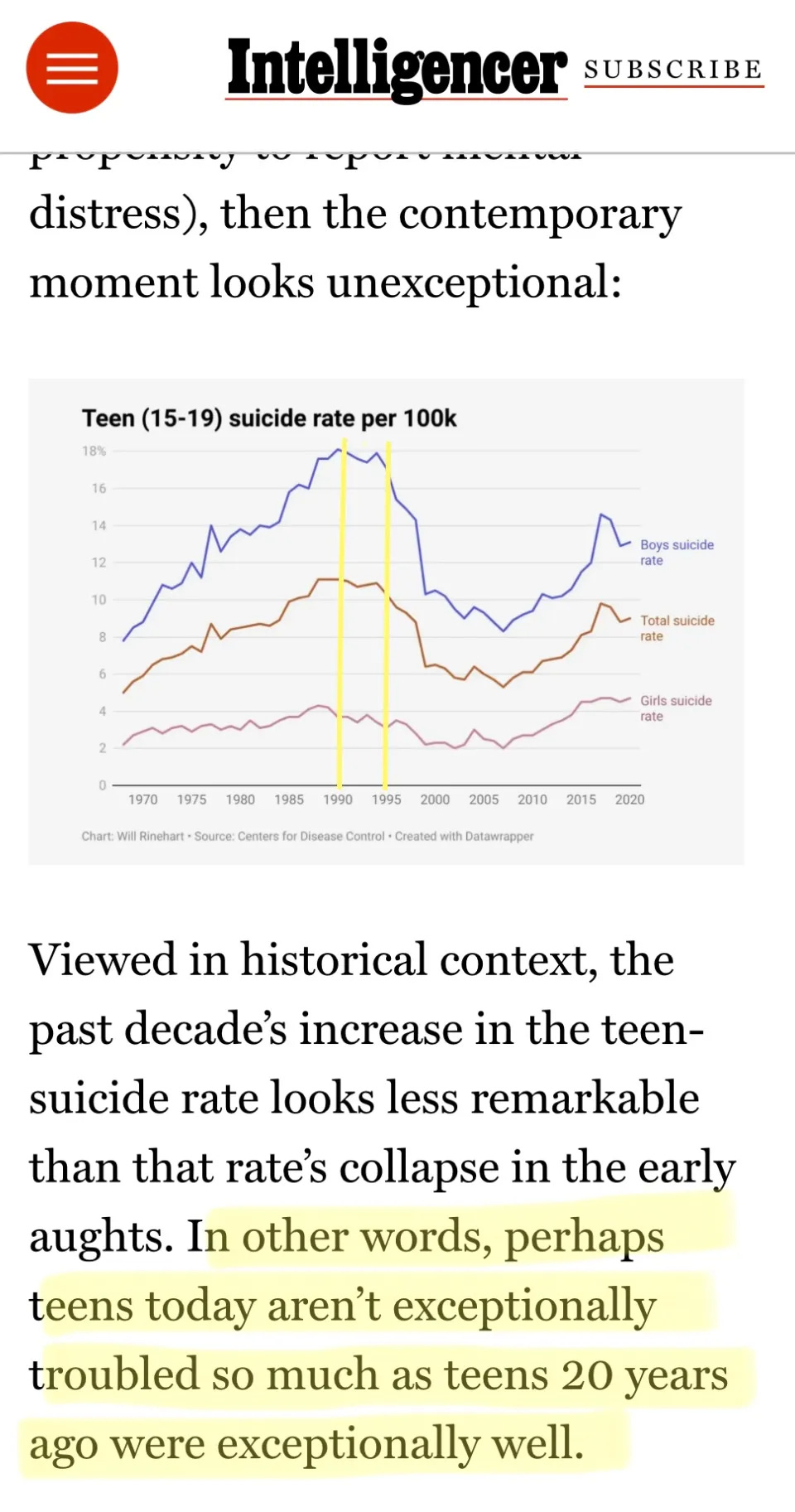

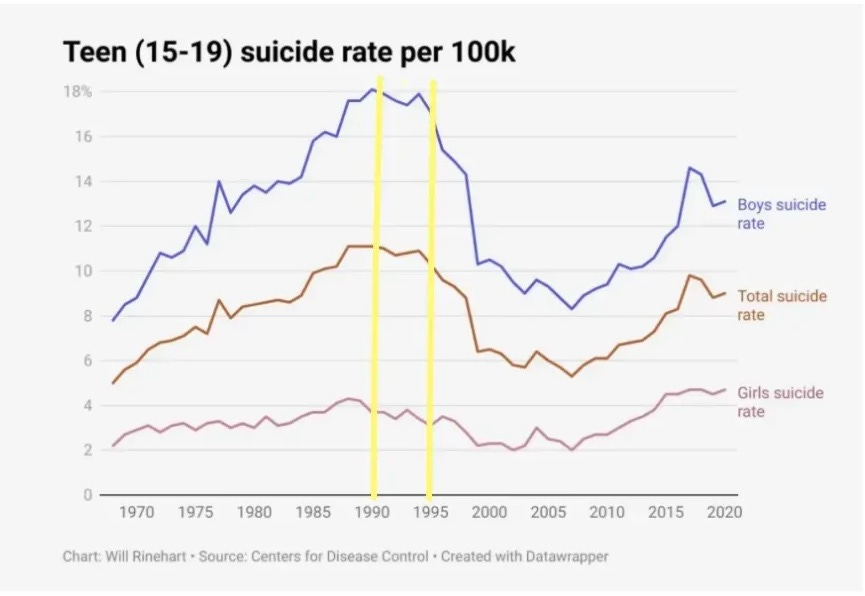

Jonathan Haidt, an author who I kinda hated around 2005 but whom I’ve since kinda come around to, has been gathering evidence that the essential mover of teen despair involves social media and smart phones, and I’m not here to dispute that. But I think it’s important to acknowledge the following perspective as well (the two vertical yellow lines on the graph are my addition):

The two vertical yellow lines I added mark the years that I, personally, turned 15 and 19, the age range of concern to the graph. Where the suicide rate dives, around 2000, I was 25, teaching 18 year old college students at the University of Arkansas, and had just experienced my first “school shooting,” which was also a suicide.

As the article says, “perhaps teens today aren’t exceptionally troubled so much as teens 20 years ago were exceptionally well.”

And teens between 1965 and 2000 were exceptionally fucked?

Heathers came out in 1989, the year I started high school. It’s a teen movie that makes comedy out of murder, suicide, and blowing up a school, and I absolutely loved it. In fact, I just re-watched it, and I laughed aloud throughout; so I guess I still love it. I must be a very bad person.

As a teenager I identified with the outsider-ness of the outsider characters (despite them being wealthy, while I was quite not!). I liked Winona Ryder’s Veronica especially, but I liked Christian Slater’s psychotic JD too. Not to labor the plot, but Veronica also sees something in him, and she doesn’t really sour on him until it becomes clear he’s not going to stop killing her “friends.”

I did not and do not share these characters’ murderous tendencies, but that said, the murders-made-to-look-like-suicides did seem funny and “just” to me, in the realm of fiction, where these dark fantasies belong. It is horrible, trying to survive and grow under the bullying of ruthless “cool kids.” There’s satisfaction in seeing those jerks fictionally smote.

Adults, at the time, seemed not to quite get the movie’s genius. At the time of the film’s release Roger Ebert wrote:

I approach "Heathers" as a traveler in an unknown country, one who does not speak the language or know the customs and can judge the natives only by taking them at their word. The movie is a morbid comedy about peer pressure in high school, about teenage suicide and about the deadliness of cliques that not only exclude but also maim and kill.

Life was simpler when I was in high school.

"Teenagers don't have any trouble with it," the film's director, Michael Lehmann, has said of the movie. "It's always adults that are shocked." This statement is intended, I assume, in praise of teenagers.

Adulthood could be defined as the process of learning to be shocked by things that do not shock teenagers, but that is not a notion that has occurred to Lehmann.

I loved and respected Roger Ebert, but as he said: life was simpler when he was in high school (late 1950s). Later in the review he compares Heathers to the Friday the 13th franchise, as though it were all for jump-scares and gore. He doesn’t quite manage to do what he proposed: to take the natives at their word. If he had, we would have told him this film was a cathartic ambiguation and distillation of our daily reality, and that the pleasure of watching it was not *just* the fantasy of seeing the wealthy bullies revenged upon for their cruel deeds, but also sharing in an act of public recognition that this is our world and it is fucked.

Suicide as a social contagion seemed fair fodder for comedy to our teen brains — it was like when your mom asks you “if all the other kids jumped off a cliff would you do it too?” (The movie actually uses a version of this line, but it’s Veronica, not a parent, asking it of a suicidal Heather, and the Heather replies sadly, “probably.”) The popular kids seemed to be killing themselves, so the less popular kids followed them off the cliff. Or seized the power vacuum to become the school’s new “queen.” Or tried to leverage the tragedy into their Harvard application package.

The movie features an in-story pop hit by a band called “BIG FUN” that sings “teenage suici-i-ide” followed by the muted parenthetical (“don’t do it”), which felt like a wink at the ubiquitous and ineffective “just say no (to drugs)” campaign of the era, the way media panic doubles as hype, and at adult cluelessness in general.

There’s a lot of adult cluelessness in this movie: parents interact with their teenage kids by reciting repetitive, ritualistic banters, with the formulaic tone of catch-phrases from sitcoms; the warden-like school principal compares suicide to “PCP and switchblades” (other problems he’s dealt with in the past), and figures a half-day off school would be acceptable for a cheerleader, but only an hour early release for a popular girl. (The football players’ deaths mean everyone gets a whole day off.) The “hippie” teacher wants everyone to talk out their feelings and tries to turn the suicides into a sit-in-like “media event” where she leads the students in chanting “the whole world is watching” for the news cameras she invites, but which she pretends appeared by chance and surprise. The same teacher later advises Veronica: “whether to kill yourself or not is one of the most important decisions a teenager can make.”

It’s bizarre and hilarious, and it’s also what they used to say about sex: important decision, you could get AIDS and die, don’t take it lightly! In Heathers there is a lot of sex, mostly non-consentual. This movie is very, realistically, rape-y. Or, as it was called at the time, “date rape”-y. There are a lot of scenes where things “get out of hand” very quickly and people are suddenly raping and raped and the raped fear stigma and shame, while the rapists strut and brag or, if denied, spread socially-poisonous “slut shaming” lies. In this world there’s no way to talk about sex except “I just wanna get laid” and “they said they had a sword fight in your mouth.” Everything is degradation.

This movie is also very, realistically, homophobic. The “bad guys,” the two football players who are also bullies, are the most homophobic, but even the film’s heroes ascribe to the casual bigotry of those times.

As they’re planning to set up the two jocks so they look like gay lovers who’ve killed themselves together because the world could not accept their love, they plant “homosexual artifacts”: a magazine with nude men, a heart-shaped box of chocolates, a Joan Crawford postcard…

J.D. : And here's the one perfecto thing I picked up. Mineral water.

Veronica Sawyer : Oh, come on, a lot of people drink mineral water, it's come a long way.

J.D. : Yeah, but this is Ohio. I mean, if you don't have a brewski in your hand you might as well be wearing a dress.

This punch line is drilled home when the police find the bodies:

- Officer Milner: My God, suicide. Why?

- Officer McCord: [holds up bottle of mineral water found next to one of the bodies] Does this answer your question?

- Officer Milner: Oh man! They were fags?

But notice that Veronica said “it’s come a long way” — mineral water has “come a long way,” from the “lowly” negative association of being a “gay” drink. It’s an at-the-time-unremarkable statement equating gay with “bad,” from an era when “that’s so gay” was a common expression, used to mean “stupid, bad, embarrassing” — akin to today’s “cringe.” Mineral water was making social progress, but gay people still had a long way to go.

When the jocks beat up a “nerd” who accidentally stepped on one of their feet, their first act is to force him (by physical brutalization) to say that he likes to suck big dicks. (The “nerd,” for the record, parries admirably, and defeats them rhetorically, although he may have paid for that little victory with a dislocated shoulder.)

When the jocks first see JD, the new kid, talking to Veronica, they go after him by calling him “fag” and asking about his “boyfriend.”

And when they do, he pulls out a real gun and shoots twice.

Blanks.

You find this out in the next scene:

- Heather Chandler: He used a real gun, they should throw his ass in jail.

- Veronica: He used blanks. All he did was ruin 2 pairs of pants, maybe not even that... can you bleach out urine stains?

Talk about cinematic moments that would be received differently today.

But the moment in the movie that has disturbed and haunted me all these years is at the funeral of these two football players, where one macho jock dad of one of the macho jock victims acknowledges his son’s “confession” and weeps publicly, declaring aloud to the church, “My son is a homosexual, and I love him! I love my dead gay son!!”

Christian Slater’s character, JD, scoffs at this and wonders whether the dad would still declare his love if his son had “a limp wrist with a pulse.” Veronica laughs and then is confronted by a tiny turned head revealing the weeping, confused face of a little girl who we might understand as the dead teen’s little sister.

Veronica is brought back to reality. Nonetheless, in that scene, the tone of movie feels like it is mocking the grieving father — HE’s the joke. JD and Veronica laugh not just at how hypocritical they think he is, but at how embarrassing it is, to proclaim love for your gay son. They’ve driven him to humiliation and like most teen humiliations “it isn’t even true.” That little girl’s reproachful glance isn’t against the joke, it’s against Veronica’s too-loud laugh. If anything we’re meant to pity the child for having to bear the horrible stigma of a gay brother, on top of his death.

There’s more: the overweight and socially isolated student the others call “dump truck” and work very hard to humiliate; the kids who check out and get stoned pretty much always, the kids who don’t dress well, who wear glasses, and don’t go on dates and are still virgins, in a social scene where “cool” people drink a lot and get rape-y.

The way Veronica ends up killing her “friends” alongside JD is a lot like how people in this story end up having sex: they get lied and seduced into it slowly then quickly; then they’re told they really wanted it all along. After all, JD says, if you really didn’t want to kill someone, you’d have fought harder not to. Veronica gets pulled into serial murder the same way teenage girls got pressured into sex. And when she retakes control and cuts him off, he wants to kill her. It’s fucked up, but it rings true.

This was teen life at the peak of the suicide rate, in darkly comic parable form. The vast majority of teenagers didn’t kill themselves, but the rate was higher, and we should ask why.

I reflect on what changed, what was different during those lower-suicide years between ~1996 and 2012 (the year Haidt points to as the crucial moment, which overlaps with the moment when smartphone use and social media became ubiquitous). And there is, at least based on my experience, an answer. And it’s related to Haidt’s.

Between 1996 and 2010ish you could go online and find community with fellow weirdos, and your real life bullies probably couldn’t find you there. By 2012 that had changed.

Between 1996 and 2010ish “online” was a place you “went” when you were home and probably at a desktop computer with a sluggish modem. It couldn’t follow you into the real world. It might’ve felt “addictive” but its limits were strict — and it wasn’t purposefully addictive: no one was trying to game your brain with reinforcing feedback to keep you online as much and as long as possible.

Between 1996 and 2010ish going online meant you could be anyone, male, female, elf, otter, anthropomorphic lemur, whatever, and there really wasn’t a way to tie your online life to your real life. The digital breadcrumbs just hadn’t been dropped yet.

The ability to express oneself through an alternate identity was healing for many people — but by 2012 or so, online identities had been so swept into the commercial need for “real verified identities” tied to credit cards and addresses, that your real life bullies could find you.

And the worst of them also found their online groups of fellow-bullies and so now you’re being bullied not just by a handful of dickheads from your own high school, but an organized collective of dickheads who compete to see if they can get you to kill yourself.

What was that dip in suicides, that era of relative mental health and thriving? Perhaps it was the promise of the early internet, delivered: a reprieve from the horrors of Heathers, a window in time during which teens could enjoy and benefit from the good parts of global connection and information exchange without all the bad parts that followed, as things got monetized and made worse.

I theorize that, yes, “teens 20 years ago were exceptionally well,” because they grew up, more or less, using versions of the internet that were more open and free and not yet built for profit. They could connect with people and ideas and art and culture, they could create and share and make an impact, and they could escape the mainstream conformists and their bullying, because the internet was not yet mainstream.

And then, around 2012ish, being online went mainstream. We went from “computers are for nerds” to every Heather having her Instagram. Instead of spoofed handwriting passed as a joke-note, you’d be humiliated with a spoofed snapchat account. The overwhelming pressure to conform, to watch what you say, to join mobs so you don’t end up the victim of one, not to mention the pressure of comparing yourself and feeling inadequate — all of that went from something in the real world that you could meaningfully escape to something that now follows you everywhere, inescapable, no respite. And now, the bullies are more likely to dominate the online world as well as IRL.

I’m not a social scientist, but I am (proudly) a nerdy uncool overweight nonconforming outsider whose school experiences were hell and whose birth year granted me an interesting vantage point from which to watch these changes. I think the golden age of the internet, while it slipped us by, also granted some teens some high school years that were a little better. And I think if we could somehow get that back: a non-manipulative, non-monetized, free and open internet where you can find privacy, we could save lives.

OMG, so insightful, Amy. I started going online in 1994, and it allowed me to find a sense of connection with other people. Before that, I had none. I was definitely a weird, socially awkward kid. Now that the internet has become so dystopian, I often feel nostalgic for the old internet. Being able to read a brilliant post like this though reminds me that there are still some really great things on the internet today.

Nailed it.

My 15-19 was 5 years ahead of the peak, but I played out the rise. I gave non-explicit suicide a few goes. I was nearly successful. I also remember the early internet well, visiting BBSes (bulletin board systems) often. The internet has so much promise before capitalism seized it completely.

Culture bends all to its will, and this is why technology will not save us alone. We need changed minds, not old minds with new programs. Then again, I am not a social scientist either. But we have front-row seats on how it's playing out.