To me, part of seeking out our “humanity” is shedding the superficial categories that separate us from our fellow humans.

Those “superficial” categories include some things that are very dear to many human hearts, however: race, religion, nationality, language, culture, sub-culture, status, gender. And it is arguably our passion for these “superficial” attributes that makes us human.

The paradox of embracing a core identity (human) whose defining feature is social sorting (Jewish, male, rich, gay) can be resolved by abstracting out all categories as social indicators of varying sizes and pressures.

So, metaphorically, religion, nationality, and gender could all be imagined as “necklaces” of varying visibility, burden, and social appraisal. You could have a very discreet necklace of great worth in the eyes of yourself or your fellows, and you could have a clunky and unweildy necklace that is despised by others yet valued by you (or vice versa), and you could have an unmistakable albatross swinging from your neck that you (and everyone else) wishes to separate from, and so on. And your relationships to these (intersecting!) necklaces draped upon you by fate and choice affect your life and mind and the lives and minds of others you know.

I seem to be arguing that the “act of indication” is the medium and the “content” of what is indicated is the message, which immediately prompts me to wonder if, as McLuhan’s voice eternally chants, the medium is the message, and the sorting itself is (much) more important than how one is sorted — and that for humans, it doesn’t matter where in the social order you (or others) land, so long as there is order.

There may be truth to this, in which case the desire for stable categories might be a feature of human nature, even if the categories considered real or acceptable change from culture to culture, as one group might consider only “boy” and “girl” acceptable categories, while another group might include other categories… yet they still insist on categories! — it’s unlikely for a large group of people to accept that people are people, gender signals random, and pronouns are meaningless, though an individual certainly can. But a group seems to need its signifiers and categories and therefore demands labels, so despite the appealing simplicity of “human,” we probably have to navigate cis-female and trans-man and non-binary and so on, if we are not to be constricted by “girl” and “boy.”

The sorting itself is the thing we all share. It’s a condition universal to all humankind. No matter the number of stars on your belly, you’re still a Sneech.

Cartooning permits an interesting view of the human condition in part because it exaggerates, and in part because it generalizes. Cartooning does both of these things very selectively, yet guided by emotional-subconscious-weirdness.

For example:

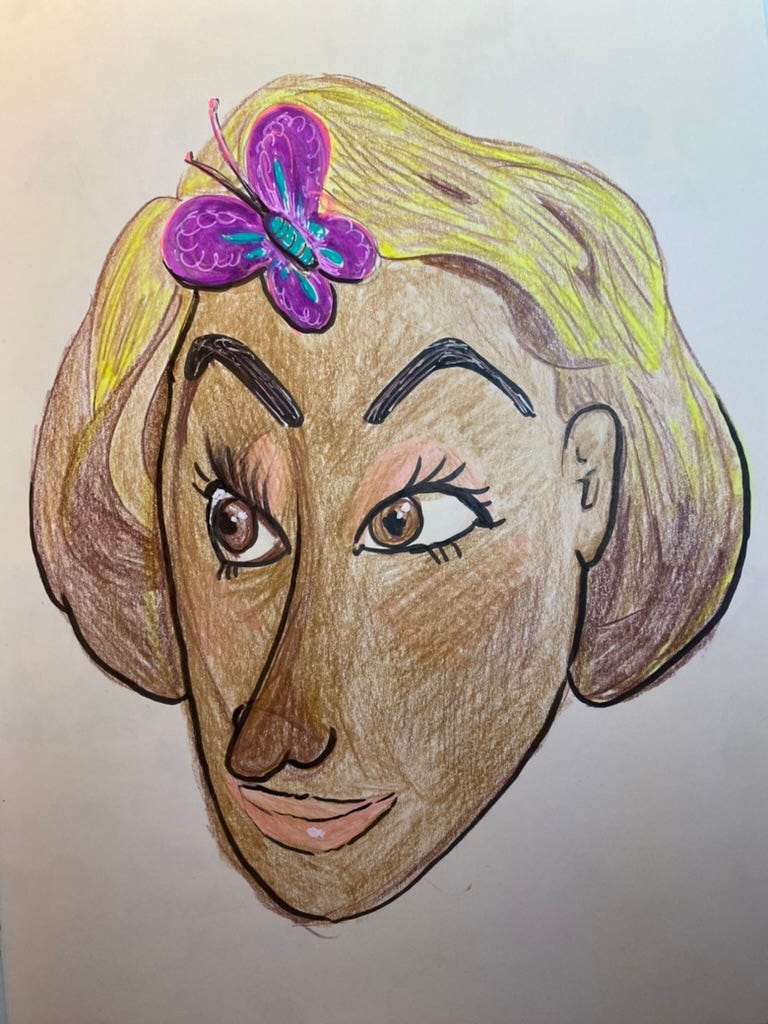

In cartoons, girls have eyelashes. In real life, almost everyone has eyelashes. But you put eyelashes on a cartoon and you’ve made it a girl.

In real life, someone whose eyes took up half of their head would be horrifyingly deformed. In cartoons, they are “cute.”

In cartoons, French people wear berets and Mexicans wear sombreros, boys wear ballcaps and girls have ponytails, and eyebrows occasionally float in the air above one’s head.

On the other hand, in cartoons, a horse can sword-fight and a human can fly!

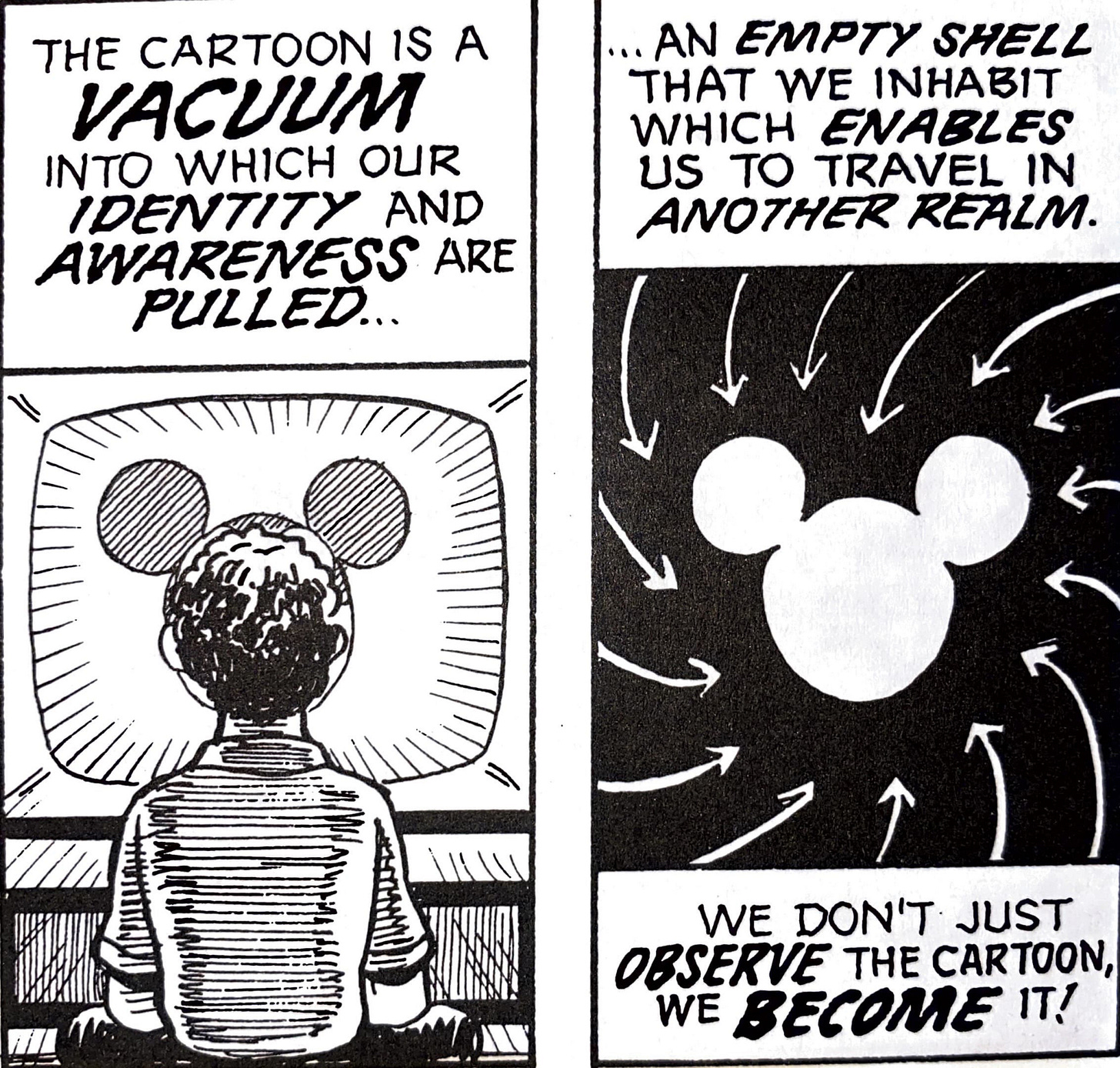

Anyone could be under Spiderman’s mask, with its basic human head-shape, its two emotive but generalized spots for eyes where otherwise categorizing facial features might be. You can be Spiderman, no matter who you are.

But while cartooning allows the universal self to come through — the necklace disappears! — cartooning also allows for blanket stereotyping: the necklace is all you see!

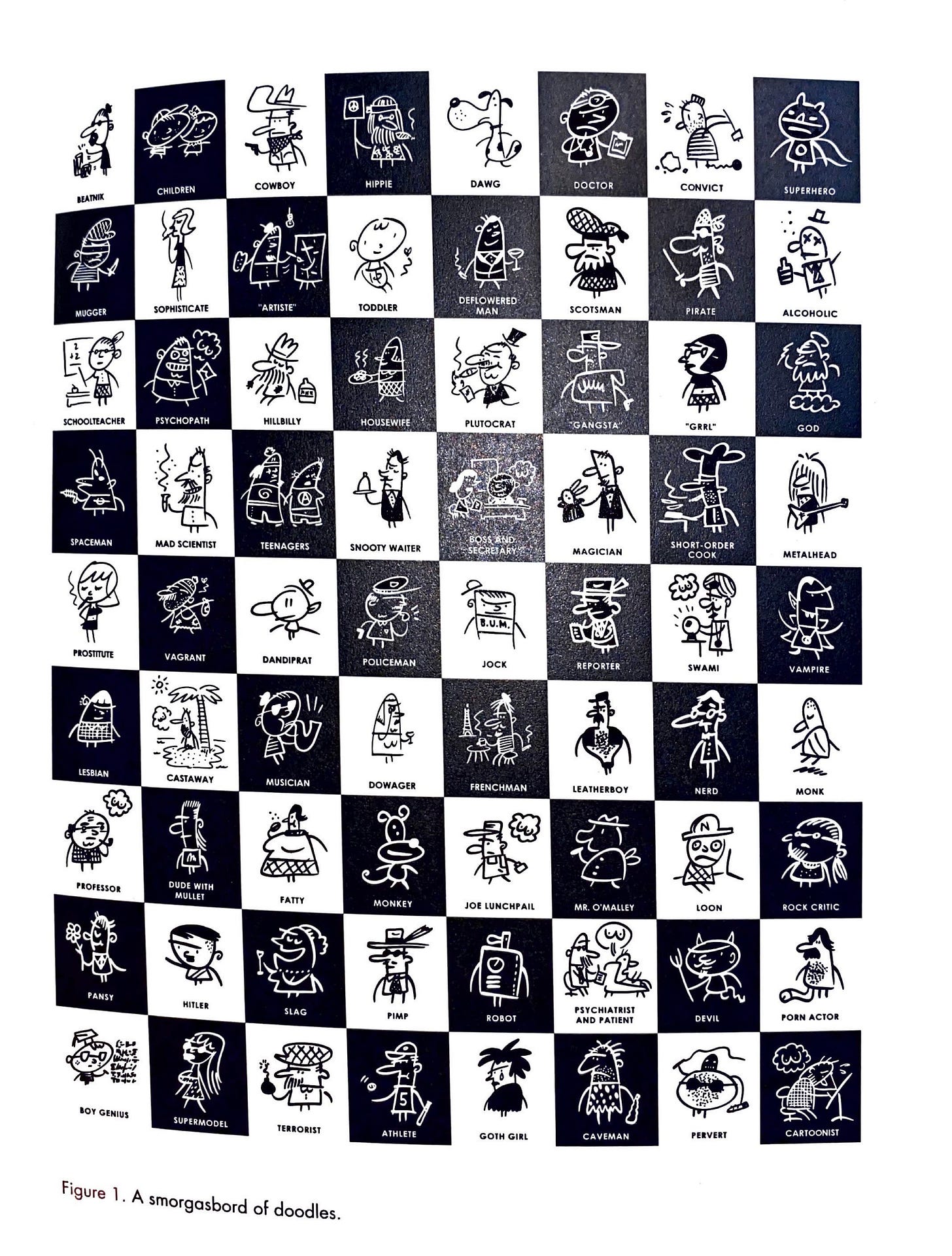

Ivan Brunetti’s Cartooning: Philosophy and Practice is an excellent guide that I never use when I’m teaching my comics classes, because on one page he does a full frontal burlesque on the third-rail of undergraduate politics — stereotyping.

Yikes, right? Yet even if you find half of the drawings on that page problematic, they nonetheless communicate. In other words, even though some of the drawings are offensive or merely stereotypical, your brain still knows this language. It’s that weird language of comics, in which smelly things manifest vertical wavy lines with a couple little infinity-sign-like flies (imagine if that happened in real life! ha!) — And even though an “Alcoholic” or a “Lesbian” or a “Professor” or a “Terrorist” could look any number of ways, these little doodles short-hand the stereotypical defaults, for all their faults.

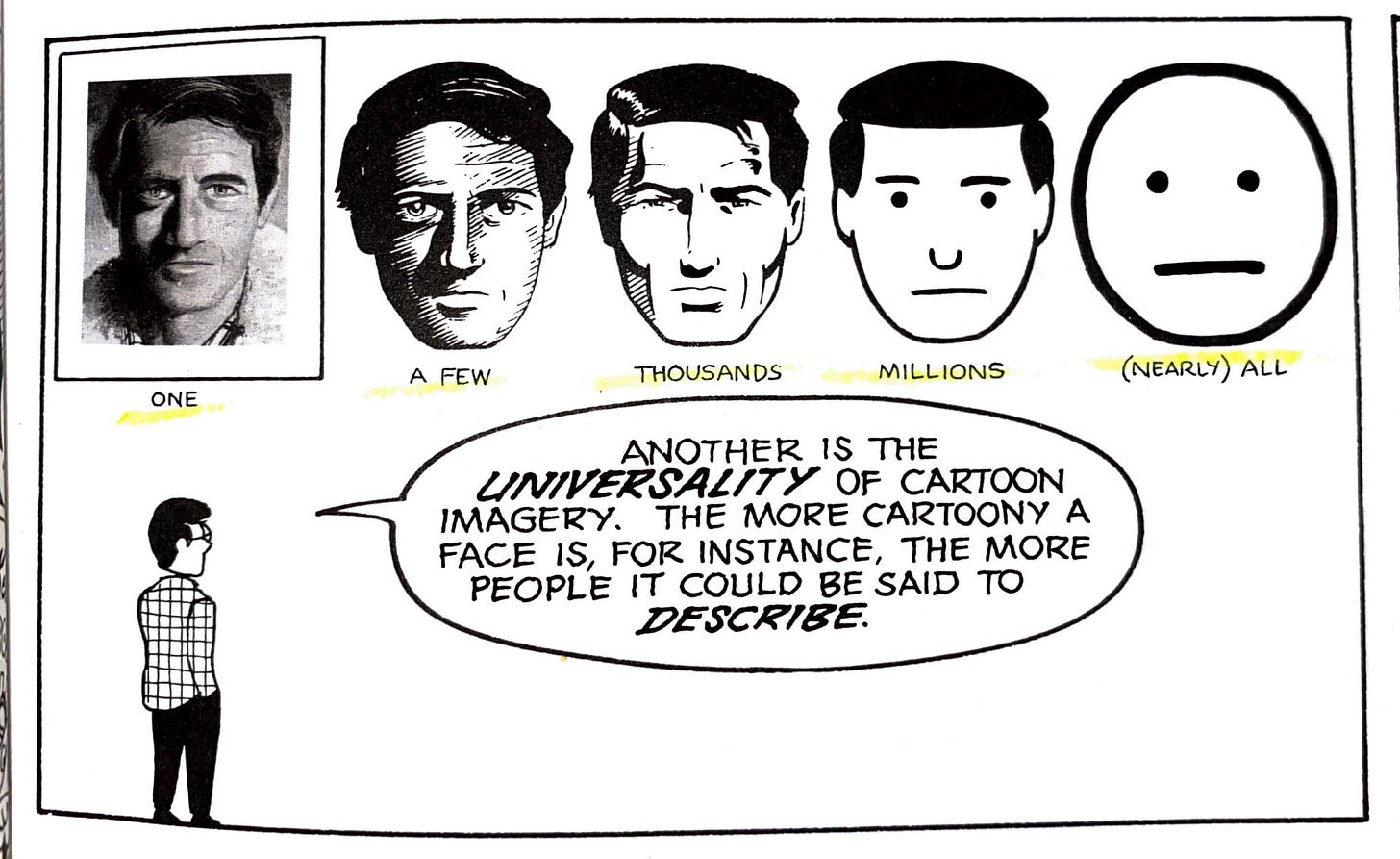

The same short-handing has another face, though, one more similar to Spiderman’s: a lack of realistic and/or specific features means generalization, and what is general can be universal, and what is universal, can be you.

On the premise that you can identify more easily with a character who is “like you” (whatever that means to you): the more generalized the character, the greater the number of people in the world who can identify.

This is Scott McCloud’s argument in Understanding Comics: that as images become more iconic, they become more inclusive. A photorealistic drawing looks like one or maybe a few people in the world. But the less realistic it becomes, the more people it could be. Until you get to a stick figure, which could be almost everyone.

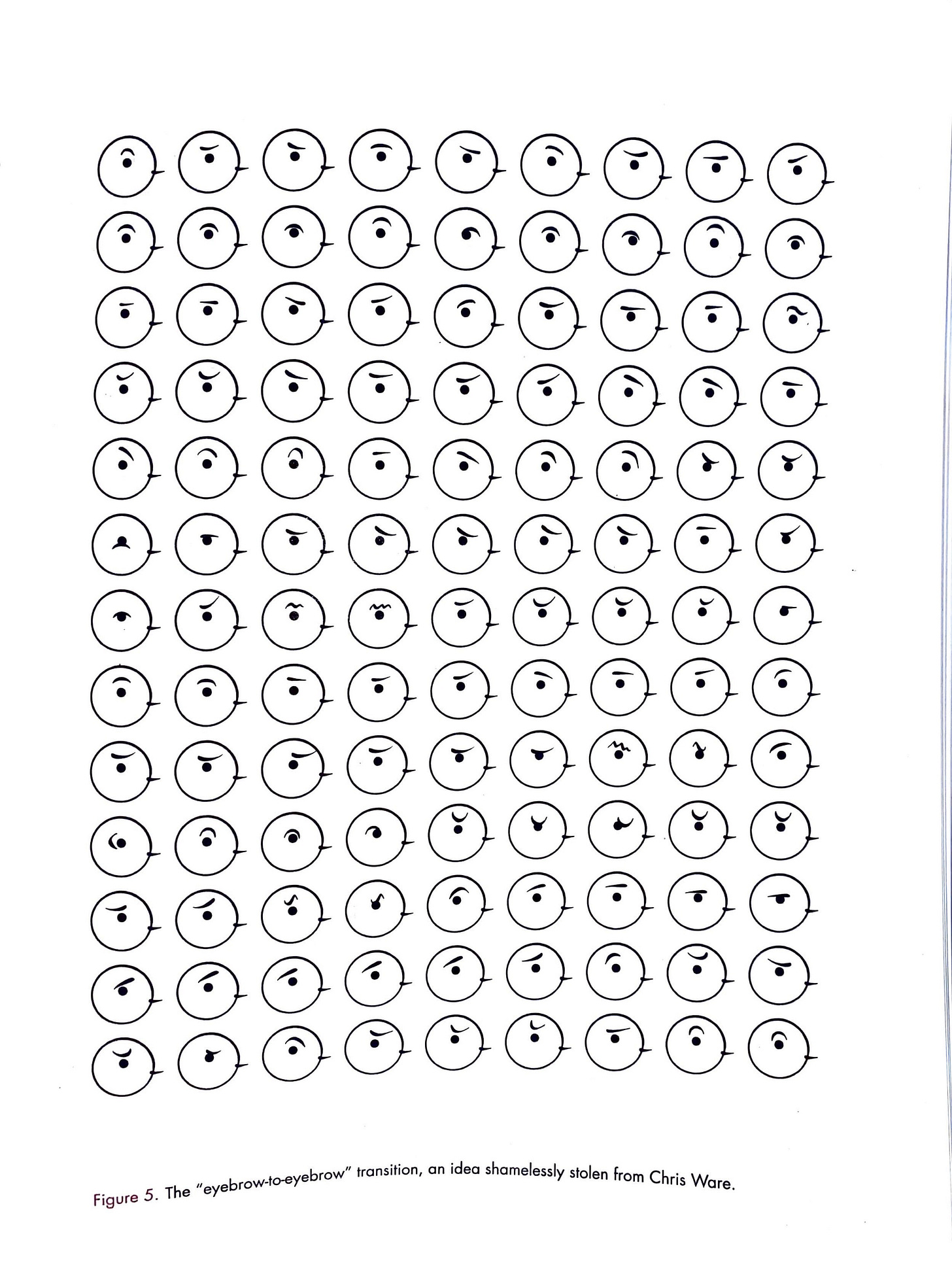

Even Brunetti includes a page of facial expressions in his guide formed only by a static circle (for “head”), a static line (for nose) and a static dot (for eye). Then eyebrows (all of which thankfully stay on the face) vary to create different emotional expressions (he credits the idea to Chris Ware).

Even if you get hung up on the lack of hair (and you don’t need to), is this repeated image a depiction of Patrick Stewart or Sinead O’Connor? Or maybe a bird. Is it a girl bird or a boy bird? Both? Neither? Who cares? Either way, in the context of a story, it can represent YOU, no matter who you are, because of that extraordinary capacity for empathy with the imaginary in your amazing human mind that lets you identify with the character!

As a child I was once scolded by an aunt for preferring Mickey Mouse to Minnie Mouse. This was an error, I was told, because I was “a girl.” Who’s to say that Mickey Mouse doesn’t represent me? He’s a fucking mouse! If I’m categorized female and I identify with Mickey, is it weirder that I’m identifying with a male character or that I’m identifying with a white-gloved pants-wearing rodent? Who’s to say Twilight Sparkle doesn’t represent my husband? He’s categorized male, sure, but how can we say it’s weird for him to identify with a girl character when he’s already identifying with a purple, magical unicorn character?

[Note: my hubs is not a Twilight Sparkle superfan; this is just an example; if I happen to see some of Twilight Sparkle’s people-pleasing anxiety in him, what’s the crime?]

Just as comics are an interesting mash of Word & Picture and an interesting mash of Universal & Stereotype, comics are also an interesting mash of Conscious & Subconscious — although this is true of all arts: it is impulse refined by practice.

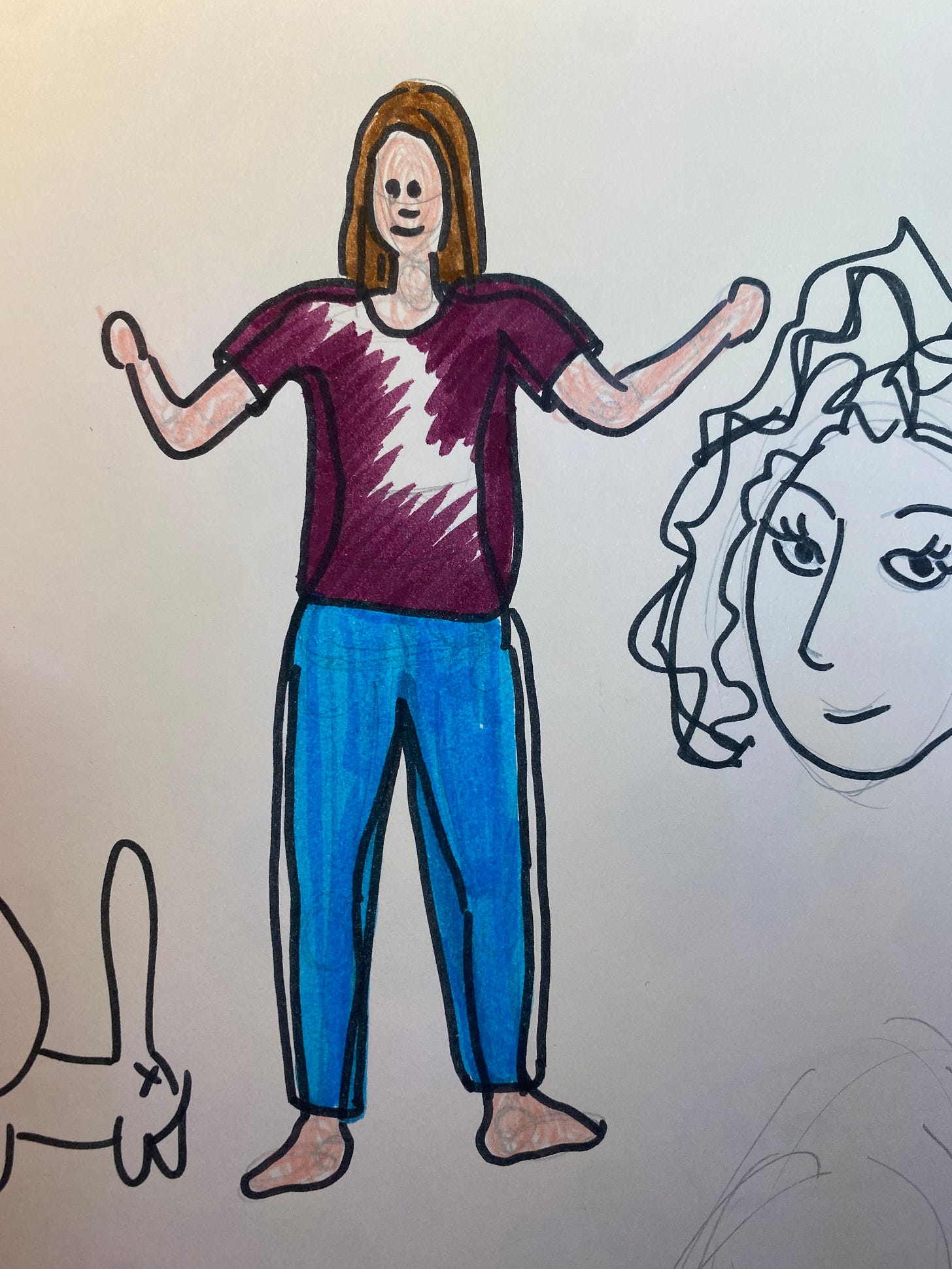

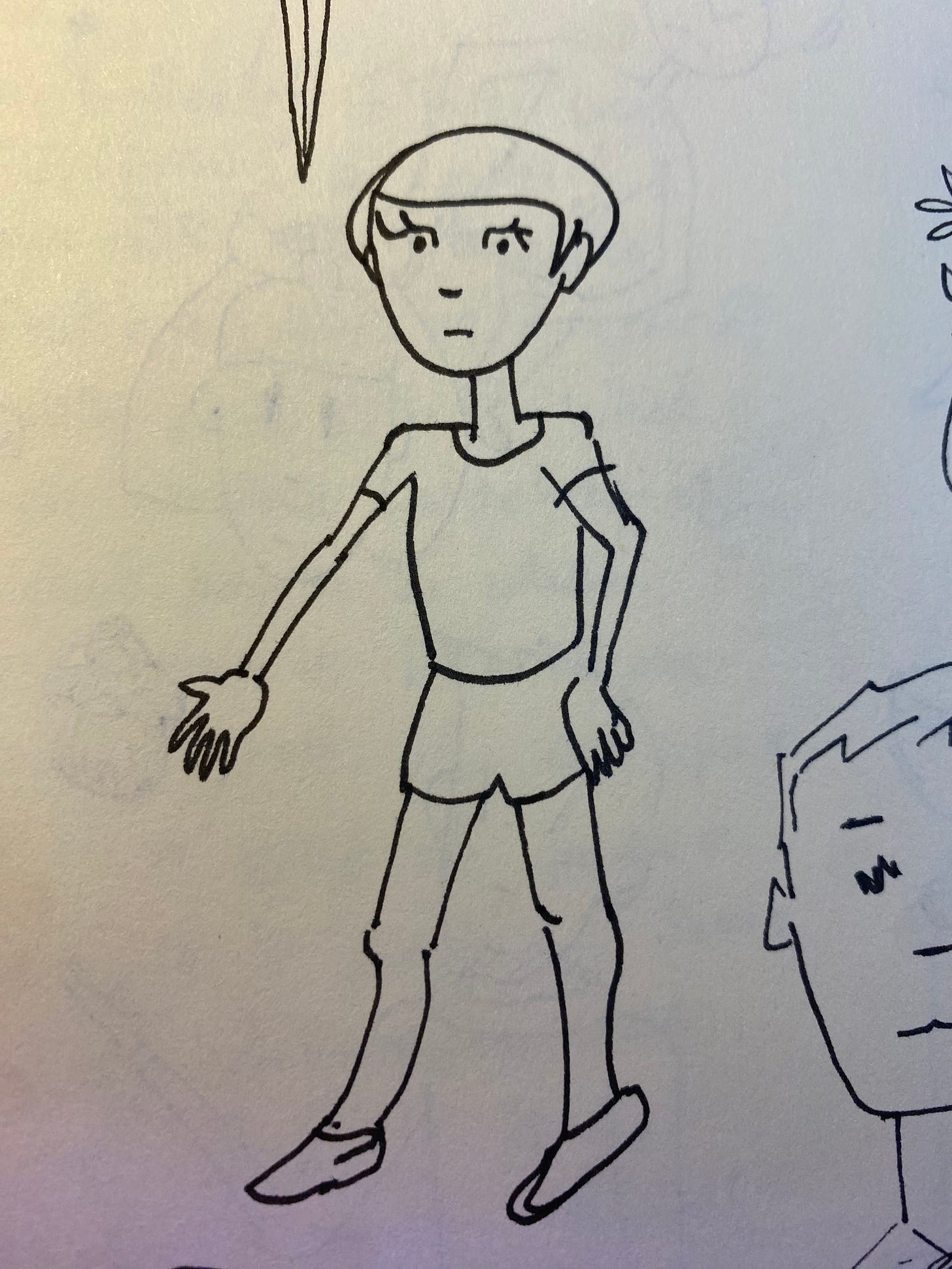

I have years of sketchbooks I can browse back through and I see a certain kind of image again and again: a person who isn’t signaling male OR female, a person who is both and neither, a person who is definitely human, and who gloriously fails to be “boy,” who righteously fails to be “girl.” And I love these figures.

It pushes against everything my eyeballs have been taught all my life about the language of cartooning. Girls - big eyes eyelashes scoop nose round lips bouncy hair. Boys - squared brow squared nose squared jaw cropped hair. But what happens when you refuse those dictates and just draw people?

What if your subconscious rebels — even when you’re trying to draw a specific person — and undermines your eyelashes, or changes the angle of that chin, or refuses the lip-shape that signals too strongly, or combines it with other signals that point the other way? When you look at these pictures, what signals “male” to you and what signals “female” and what happens when you question your first thought? What happens when you imagine you’re wrong? Can you settle your brain on “neither and both”?

Oh gosh, a few years ago, there was this thing on the internet about whether Sailor Moon was Asian or Caucasian. Apparently, white people thought she was white, and Asian people thought she was Asian. Like all anime characters, her features are not defined enough to tell us her race. That's when it occurred to me that most of my life, I'd read most anime characters as half-Japanese and half-white, like me. It doesn't make logical sense, but it made sense to my kid brain because anime itself seemed like a blending of the two cultures.

Have you read Scott McClouds The Sculptor?

It’s a phenomenal read where he finally puts a lot of his lessons into practice.

Great read, Amy!